Japan’s Economy, the Yen, and the Bank of Japan

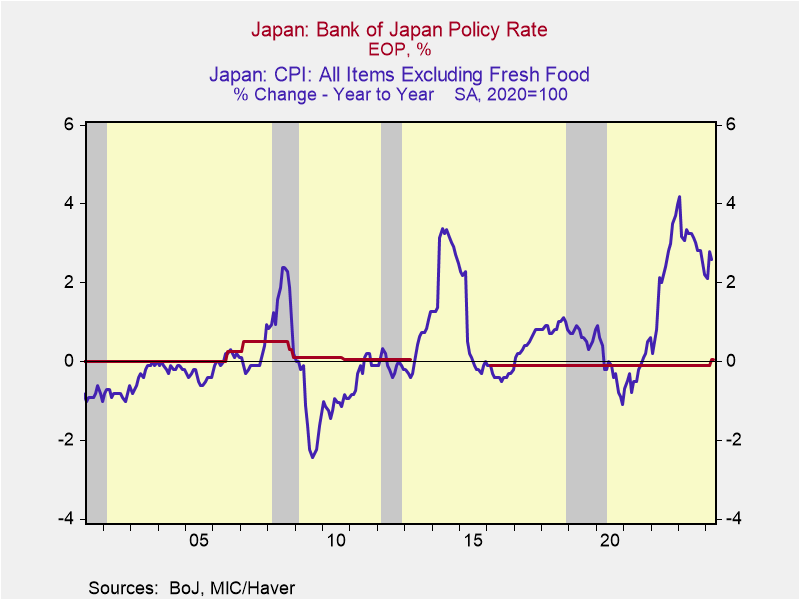

Thesis: The Bank of Japan’s policy of zero interest rates and ongoing asset purchases is contributing to a weak yen and harming Japan's economy. Raising the BoJ’s policy rate toward its 2% target would contribute to an appreciation of the yen and boost the consumer and the economy. The BoJ’s policy rate has been zero or slightly negative for years and its massive asset purchases continue to balloon its balance sheet. This has served to distort financial markets but has not stimulated economic activity. The BoJ’s policy rate is now more than 2 percentage points below inflation. In other advanced nations, a rise in the central bank policy rate involves tighter monetary policy that weakens domestic demand. In Japan, following many years of zero or negative rates and asset purchases, normalizing monetary policy would enhance economic performance.

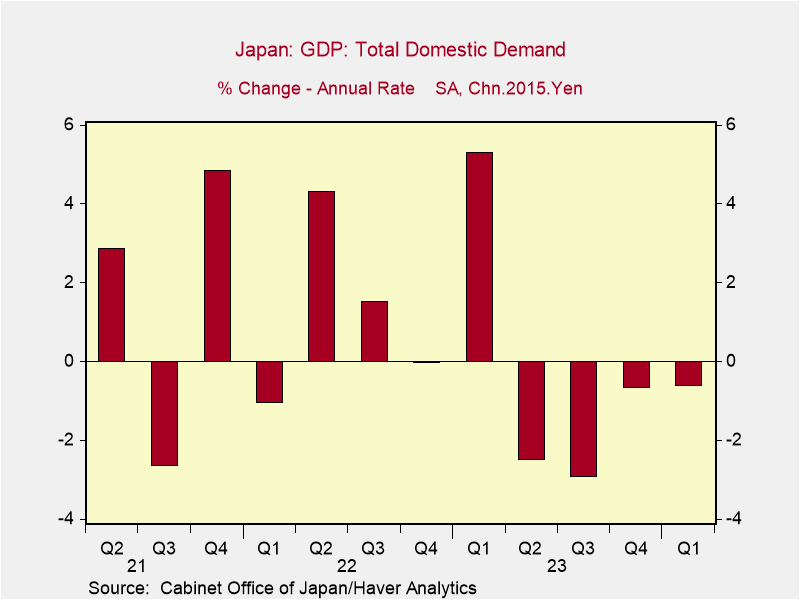

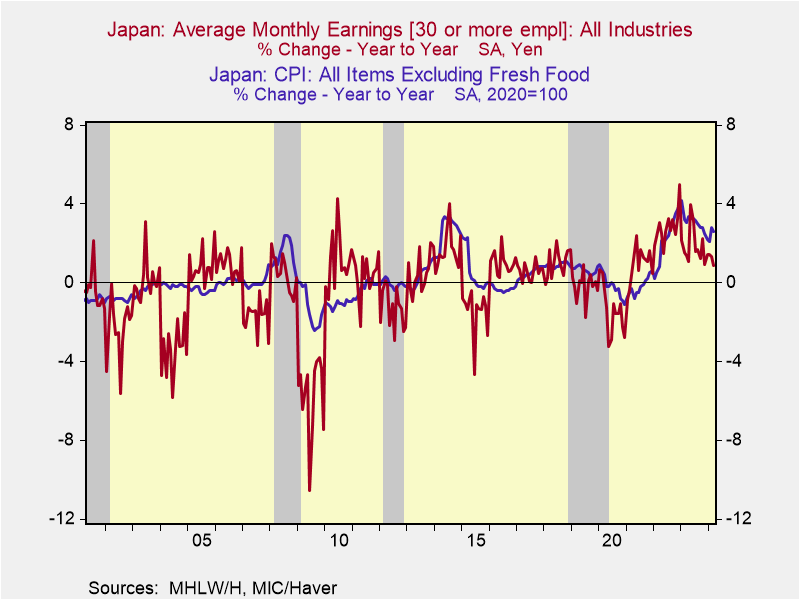

Japan's economy has struggled in the last year. Private consumption and gross business capital formation have each fallen in the last four consecutive quarters, reducing domestic demand (Chart 1). 2024Q1 was notably weak, with a 2% annualized decline in real GDP. Earnings have fallen behind inflation, cutting into purchasing power (Chart 2).

Chart 1. Japan Domestic Demand Chart 2. Earnings and Inflation

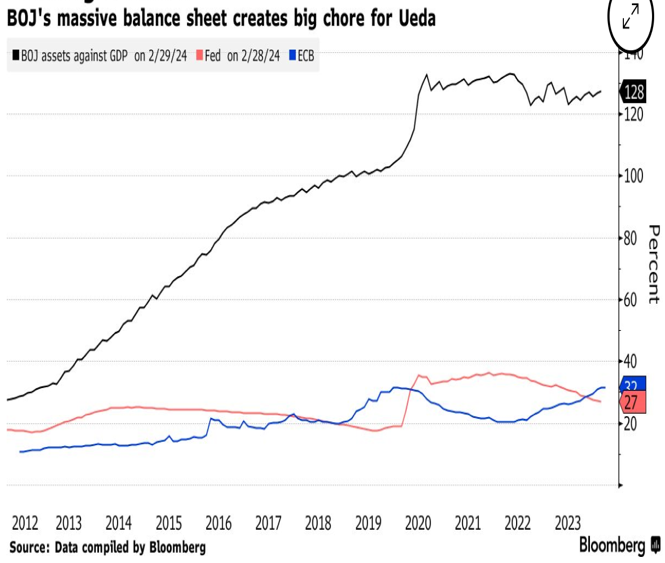

The BoJ's persistent zero (or slightly negative) interest rates have failed to stimulate aggregate demand and have served mostly to suppress debt service costs (including the government's) and distort financial markets and economic decisions. The BoJ's bloated balance sheet (its assets and liabilities) is dramatically higher as a percent of GDP than the Fed’s or ECB’s and magnitudes higher that any measure of reasonableness (Chart 3). Its asset purchases have created excess reserves in the banking system, the largest portion which are loaned back to the BoJ. The BoJ officially pays interest on excess reserves, which is tied to the BoJ’s policy rate and thus until recently has been zero. Commercial banks pay close to zero yields on deposits and generally have set rates on mortgages and consumer loans that provide positive returns to banks. Consumers lose from the BoJ’s policies.

Chart 3. The BoJ’s Balance Sheet/GDP Chart 4. The BoJ’s Policy Rate and Inflation

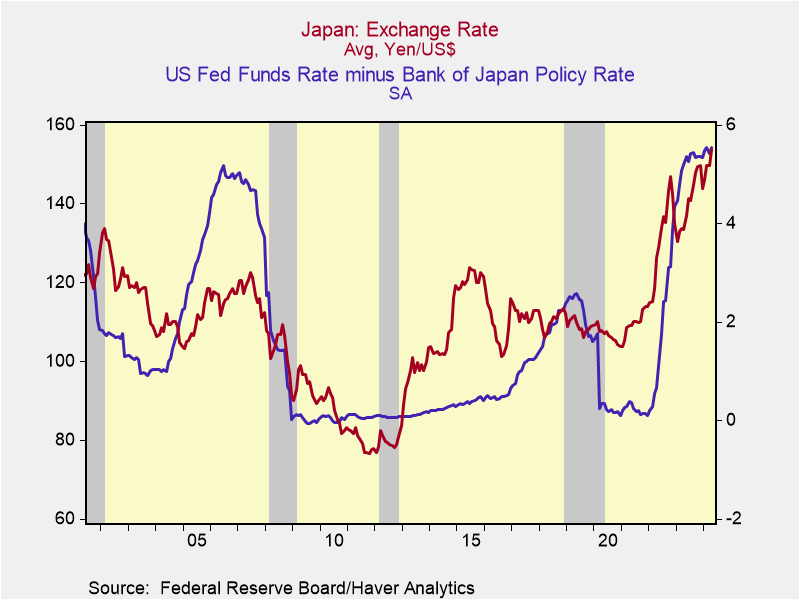

The divergent policies of the BoJ and the Fed have contributed to the marked weakness of the yen. In particular, the yen depreciated as the Fed raised rates in 2022 while the BoJ maintained a slightly negative real policy rate and its forward guidance suggested no future change. Even as the BoJ eased its yield curve control program, which allowed JGB yields to rise, the BoJ continued its asset purchases and the yen depreciation continued. Presently, the BoJ’s policy rate is more than 2 percentage points below inflation while the Fed’s policy rate (5.25%-5.5%) is roughly 2.5 percentage points above PCE inflation. Ex ante real JGBs are well below real US Treasury yields, although the comparison is clouded by the wide range of measures of Japanese inflationary expectations.10-year JGB yields have risen close 1% but inflationary expectations vary widely among different surveys and market-based measures. BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has indicated that longer-run inflation expectations are around 1.5%. 10-year Treasury bond yields of 4.5% are roughly 2 percentage points above inflationary expectations of 2.5%.

Chart 5. The Yen and Fed Funds Rate minus BoJ Rate

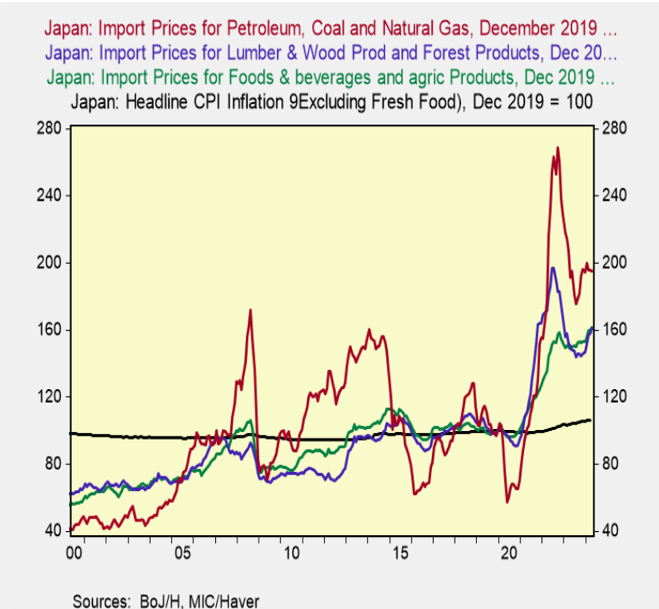

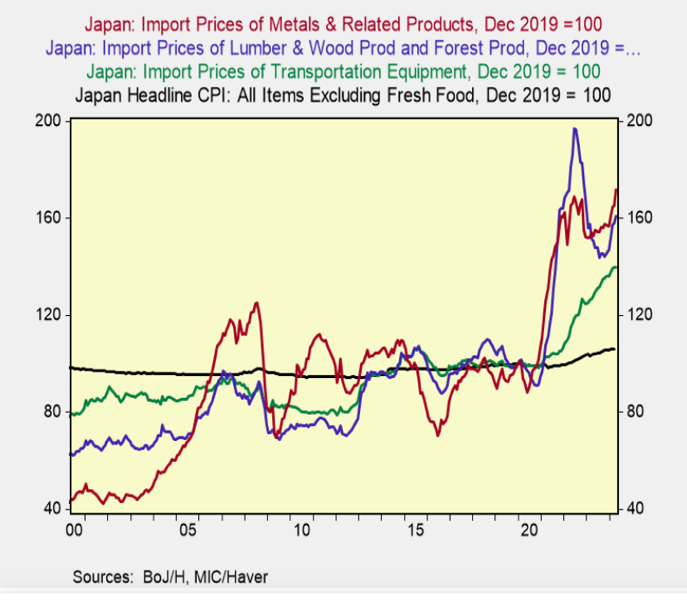

The weaker yen has benefited exporters by lowering their costs of production relative to overseas producers, but has raised the costs of imports. Japan's imports are a relatively high 18% of GDP. Japan imports nearly 100% of its oil and energy whose transactions are primarily US dollar-denominated. Prices of imported goods have risen dramatically: Chart 6 shows the cumulative price increases of goods that are consumer-oriented and Chart 7 shows cumulative price increases of goods used in production. Prices of oil and energy imports are included in Chart 6, but they affect production just as much. These high prices of imports have dented consumption and production, and they have also weighed on confidence.

Charts 6 and 7. Prices of Imported Goods, Consumer and Production-Related

Based on the higher inflation and rising inflationary expectations, and the burdens the weaker yen is imposing on Japan’s economy, the BoJ would be wise to raise its policy rate toward its 2% target and provide forward guidance that its intention is to normalize monetary policy. This would involve raising rates and implementing a gradual program of reducing its balance sheet. While the rate increases should begin immediately and continue through year-end 2025, the balance sheet adjustment necessarily must be slower. There are currently close to 3 trillion yen in excess reserves, and the BoJ holds large amounts of long-duration assets, including corporate bonds, and it also holds ETFs of equities, so a gradual unwind of the balance sheet would likely involve a 10-year program.

As the BoJ raises interest rates, commercial banks will profit from the sizable interest they receive from the BoJ on excess reserves. The steepening of the yield curve and higher interest margins will facilitate higher bank yields on deposits. Japanese pensions, including those managed by the Postal Saving System, and insurance companies will benefit. Consumers will be better off. It will take years to judiciously unwind the excess reserves in the banking system, such that bank lending is unlikely to be inhibited. The BoJ understands the negative impact of the weak yen on Japanese consumers and the economy. It’s only a matter of time before it raises rates.

Confidence will build as evidence shows economic improvement as the BoJ increases rates toward inflation and the yen appreciates. This will reinforce the yen and the domestic economy. The marked appreciation of the Nikkei has already begun to anticipate these favorable outcomes.

The Dilemmas Facing the Fed, BoE, ECB, and BoJ

Inflation in the U.S., Europe, and the UK has fallen from very high levels but remains above the central banks’ goals of 2%. Following the Fed’s, Bank of England’s (BoE’s) and European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) painful experiences of failing to forecast their higher inflations and then being forced to raise rates aggressively, they look forward to lowering their policy rates. Japan also experienced a sharp rise in inflation from near-zero that is now receding but remains above 2%, and following an extended period of negative and now zero rates, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) contemplates raising its policy rate.

When will it be appropriate for the Fed, ECB, and BoE to lower rates, and for the BoJ to raise rates? The answer varies, as each central bank faces far different circumstances.

The Fed’s, ECB’s, and BoE’s policy rate is above inflation, but by varying degrees, while the BoJ’s real policy rate remains negative. Current economic conditions vary significantly in the U.S., Europe, the UK and Japan, as do their productivity and potential growth prospects that affect their neutral rate of interest. While the Fed has a dual mandate (2% inflation and maximum inclusive employment), the BoE and ECB have single inflation mandates of 2%, but they tend to respond to real economic conditions as well. The Fed and the other CBs recently have emphasized their commitments to their 2% inflation target, but it's not entirely clear whether each would willing to pursue a monetary policy that would lower inflation to 2% if doing so may damage economic conditions. There are also currency considerations, as the US dollar has remained strong while the Japanese yen has been notably weak.

Inflation and Policy Rate Comparisons

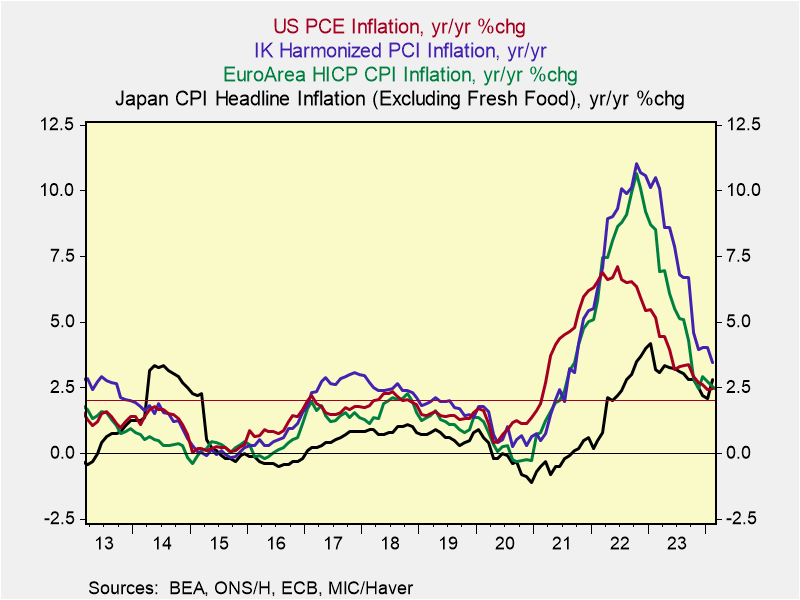

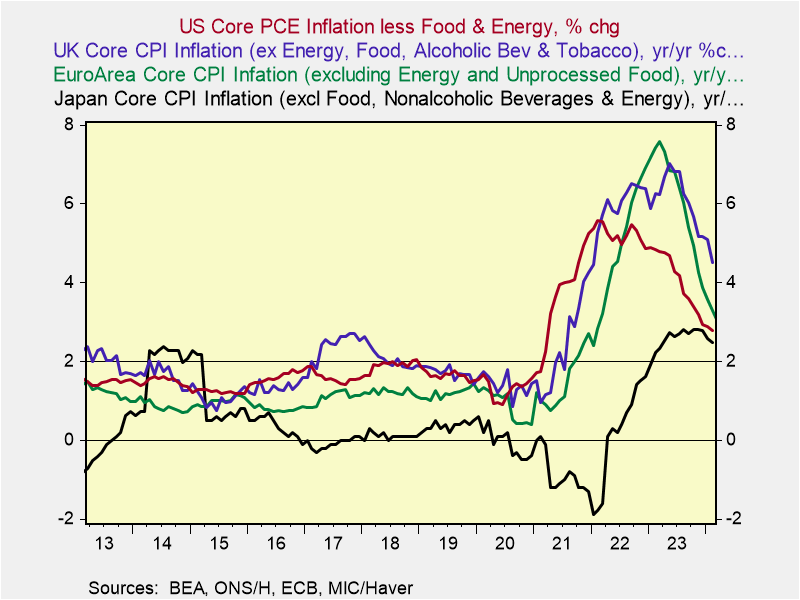

Inflation comparisons are shown in Charts 1 and 2 for both headline and core measures, and a 2% reference line for target inflation. The U.S.’s inflation is based on the PCE Price Index, the Fed’s preferred measure, while the others are CPI inflation. While inflation has subsided from high peaks, it remains above central bank targets. It soared the most in the UK and Europe. In the U.S., PCE inflation peaked at 7.2%, while its CPI inflation, which measures consumers’ out-of-pocket expenses, peaked at 9%. Japan’s inflation temporarily jumped to 4%. Currently, the UK currently stands out with the highest headline (3.8%) and core (4.7%) inflation.

Charts 1 and 2. International Comparison of Inflation

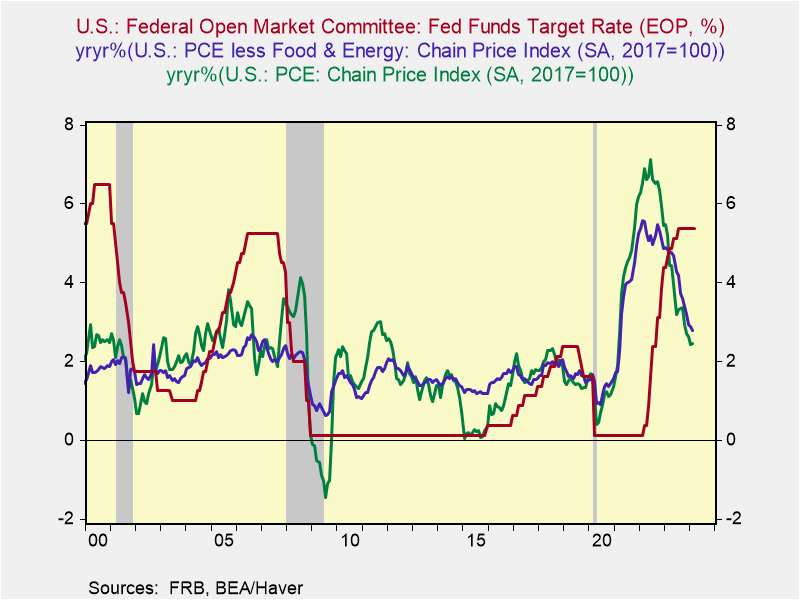

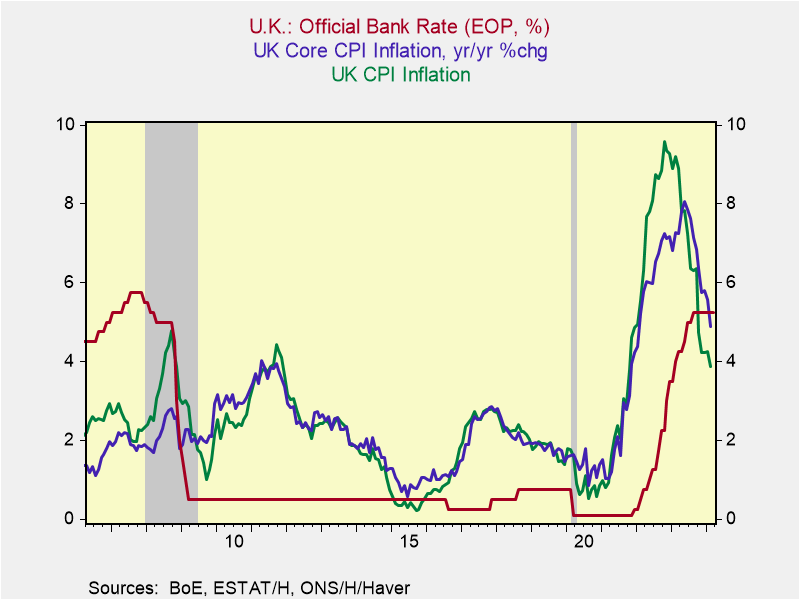

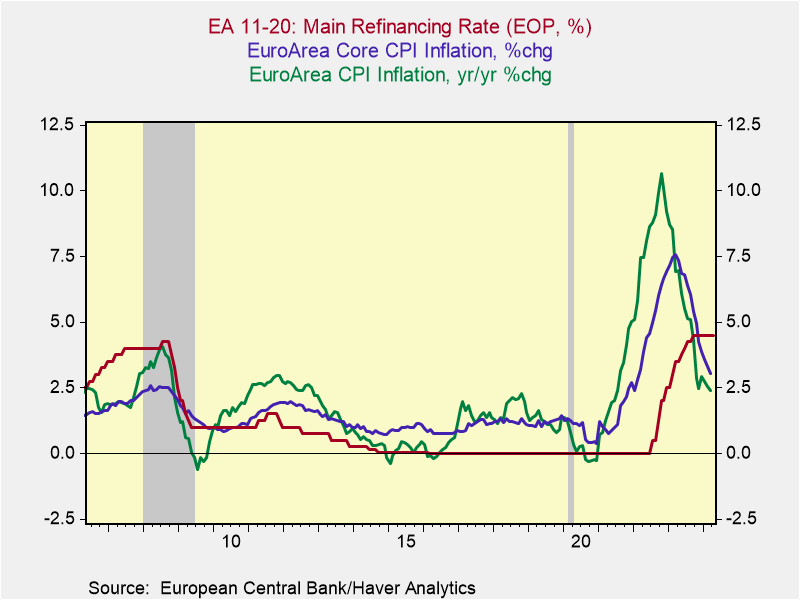

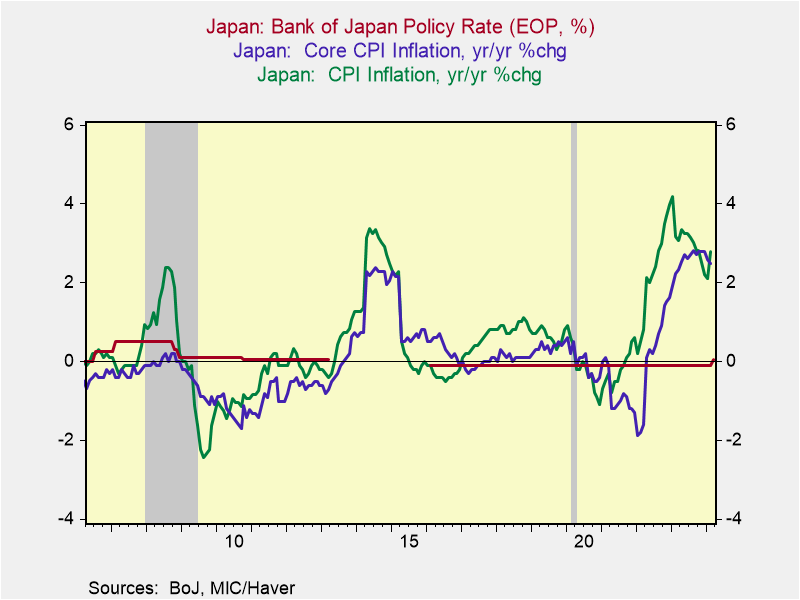

Charts 3-6 show the central bank policy rates of the Fed, ECB, BoE and BoJ relative to inflation in the U.S., the EuroArea, the UK and Japan. The Fed, BOE and ECB failed to respond on a timely basis to the surge in inflation and then raised rates aggressively in 2022-2023. The BoJ applauded Japan’s rise in inflation following a sustained period of near price stability, viewing it as a sign of economic improvement and hoping that it would lift inflationary expectations toward its 2% target.

Chart 3. Fed Funds Rate and U.S. Inflation Chart 4. BoE Policy Rate and Inflation

Chart 5. ECB Policy Rate and Inflation Chart 6. BoJ Policy Rate and Inflation

In each case, the central bank policy rate rose above inflation in 2023 through a combination of rate hikes and declines in inflation—in March for the Fed and later for the BoE and ECB. The BoJ raised its policy rate from minus 10 basis points to 0% in January 2024. Currently:

*The Fed’s 5.4% Fed funds rate (target rate is 5.25%-5.5%) is 2.7 percentage points above headline inflation and 2.6 percentage points above core inflation (Chart 3).

*The BoE’s 5.25% policy rate is 1.5 percentage point above headline inflation and 0.5 ppt above core inflation (Chart 4).

*The ECB’s 4.5% refi rate is 2.1 percentage points above headline and 1.8 percentage points above core inflation.

*The BoJ’s policy rate of 0%, recently increased from -10 basis points, is more than 2.5 percentage points below yr/yr inflation.

Assessing central bank monetary policy

The Fed, ECB and BoE have emphasized their commitments to reducing inflation to 2%. The challenge they face is determining the appropriate policy to achieve those goals. Recently, Fed Chair Powell and other FOMC members have characterized Fed monetary policy as restrictive, based on the observation that the real Fed funds rate is higher than any point since before the financial crisis. If inflation recedes further as FOMC members project, the real policy rate would rise further. The ECB and BoE also view their policies as restrictive and project that inflation will recede.

The critical issue is what policy rate constitutes "restrictive" monetary policy and what is neutral. That's a complex issue, reflecting inflation, inflationary expectations and the neutral rate of interest, which is influenced by economic conditions, productivity and potential growth, among other factors, and varies among the nations and their central banks.

Inflationary expectations in the U.S., Europe and the UK remain modestly above 2% and have been relatively sticky. In the U.S., market-based expectations of 10-year inflation are 2.3% while survey-based expectations are much higher, reflecting in part the 3.6%annualized PCE inflation in Q1 that halted the earlier trend of receding inflation. The University of Michigan consumer inflation expectations one year from now jumped to 3.5% and five years from now to 3.1%. The FRB of New York consumer surveys put inflation one year ahead at 3.0% and 5 years ahead at 2.6%. The sticky inflation has forced the Fed to back off its projection that three 25 basis point rate cuts in 2024 would be appropriate, and instead say it has delayed any rate cuts. Favorably, the Fed has confirmed its intention to reduced inflation to 2%. In Europe, a recent ECB consumer survey of 3-year ahead inflation was 2.5% for the median, but the mean expectation was substantially higher. Bloomberg survey of UK 1-year ahead inflation was 3.0%, reflecting sticky inflation. In Japan, the sustained period of near-zero inflation prior to the pandemic has weighed heavily on inflationary expectations, despite persistent efforts to raise expectations to 2%. Following years of nearly zero inflation, those expectations are rising, ever-so-gradually. In the latest survey, 83.3% of consumers expect prices to rise in one year and 80.6% expect prices will rise in 5 years. This doesn’t seem like much from the western perspective, but represents change in Japan, where expectations of true price stability had become the norm.

Real economic performance

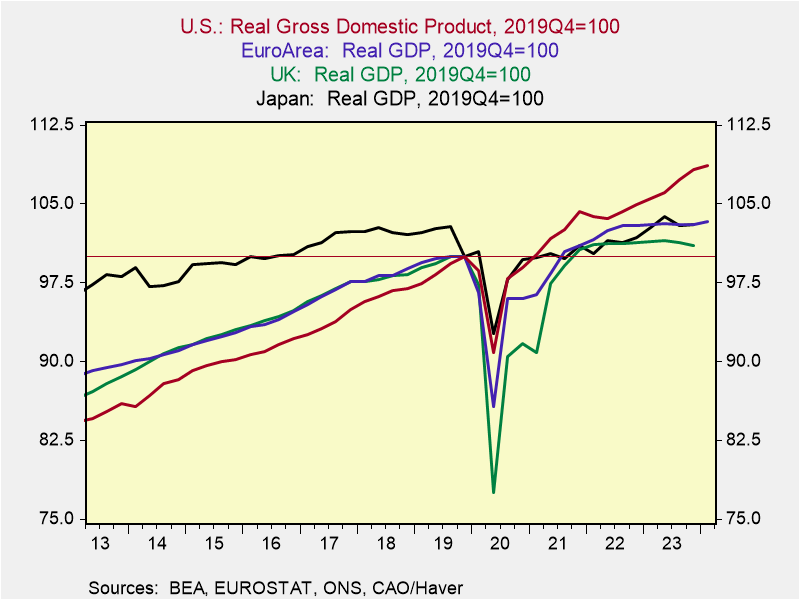

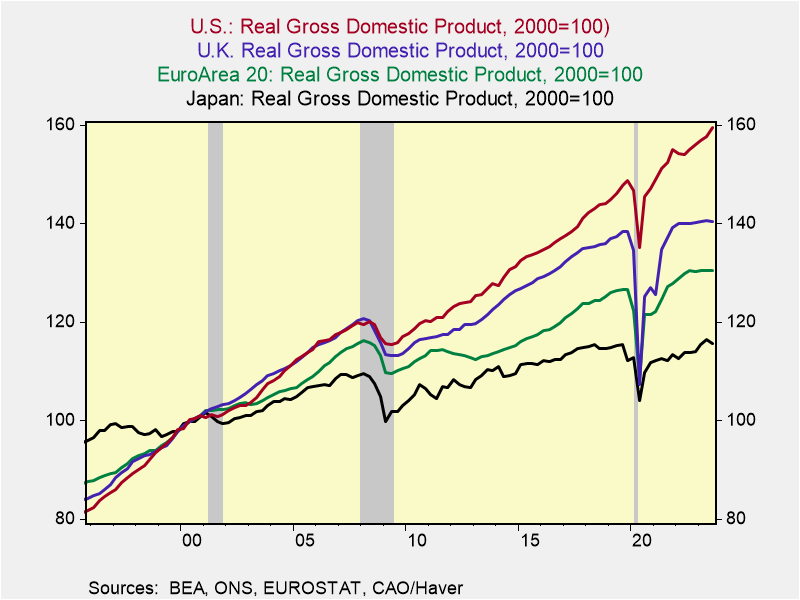

Europe and the UK have begun to recover from mild recessions in 2023, with growth in 2024Q1. Japan has continued to grow modestly faster than its longer-run potential, and U.S. economic growth has begun to simmer down following strong growth in 2023. The cumulative out-performance of the U.S.—both prior to and following the pandemic--has been dramatic, as shown in Chart 7.

Chart 7. International Comparisons of Real GDP, 2019Q4=100

EuroArea real GDP bounced back in 2024Q1 with 1.3% annualized growth following mild recession in 2023 marked by annualized RGDP declines of 0.2% in both Q3 and Q4. While consumption and gross business capital formation rose modestly in 2023, exports (-2.8%) and imports (-2.4%) both fell. Germany has been Europe’s underperformer. While its RGDP rose 0.9% annualized in 2024Q1, it fell 0.2% 2023 Q4/Q4, with sizable declines in both gross fixed capital investment (-0.8%) and exports (-3.3%). France and Italy both grew modestly in 2023 Q4/Q4 (+0.8% and +0.7%, respectively) and their pace of growth picked up in 2024Q1 (+1.2% and 1.2%, respectively). Spain was the EU’s outperformer, with 2.1% growth in 2023 and 2.9% in 2024Q1, led by healthy gains in consumption and gross capital formation but relatively flat exports. This change in economic leadership in Europe requires close scrutiny.

The UK economy also began recovering from 2023 recession, with reported increases of RGDP of 0.3% in January and 0.1% in February, following quarterly declines of 0.5% annualized in 2023Q3 and 1.2% in Q4. In 2023, notable weak sectors included exports (-7.6% in Q4/Q4) and housing construction that offset healthy gains in business investment in plant and machinery. The UK has a long way to recover. Its RGDP remains 1% below its 2019Q4 pre-pandemic level, as cumulative declines of 5.4% in exports and 2.1% in private consumption have offset 4.8% increases in gross capital formation (minus dwellings).

Japan’s economy grew at a healthy, above-potential rate of 1.3% in 2023 Q4/Q4, driven by strong gross domestic fixed capital formation (+4.2%) and exports (+3.7%) but modest declines in private consumption. In its most recent Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices Report released April 31, the BoJ projects that Japan’s economic growth will continue to exceed its estimate of longer-run potential through 2025, with resilient consumption supported by government efforts to offset higher gas prices, accommodative financial conditions that support continued employment and wage gains, healthy corporate profits and rising exports.

The U.S. enjoyed strong 3.1% RGDP growth in 2023 Q4/Q4, defying earlier expectations. Outsized gains in employment (4 million, averaging 333,000 per month) fueled rising personal income and consumption, business fixed investment posted gains and residential investment recovered following declines in 2022, and exports rose modestly despite flat global trade volumes. Growth slowed in 2024Q1, but not as much as the 1.6% annualized rise in RGDP suggests. Final sales to private domestic private purchases rose 3.1% in Q1, but real GDP was dragged down by slower inventory building and a wider trade deficit (exports rose 0.9% annualized while imports surged 7.2%). Employment gains slowed to 175,000 in April.

Economic performance, real rates and monetary policy

The neutral policy interest rate varies significantly across nations, reflecting differences in trends in productivity, potential growth, demographics and other factors. Based on recent and expected performance, the neutral policy interest rate is presumed to be the highest in the U.S., followed by the UK and the EU. Unique circumstances in Japan make the BoJ’s neutral rate more of a puzzle.

In the U.S., even though the Fed has the highest real policy rate since before the financial crisis, the economy has been resilient, growing faster than the Fed’s estimates of longer-run sustainable potential, calling into question whether monetary policy is as restrictive as the Fed suggests. As I argued in a recent Wall Street Journal

article, following several decades of a secular decline in the neutral rate of interest amid weak productivity gains, the neutral rate has risen reflecting the healthy economic growth, and a pickup in productivity and potential growth, which suggests the Fed has less room to ease rates and remain consistent with its objective of lowering inflation to 2% (“The Fed’s Latest Problem: A Strong Economy”, March 4, 2023).

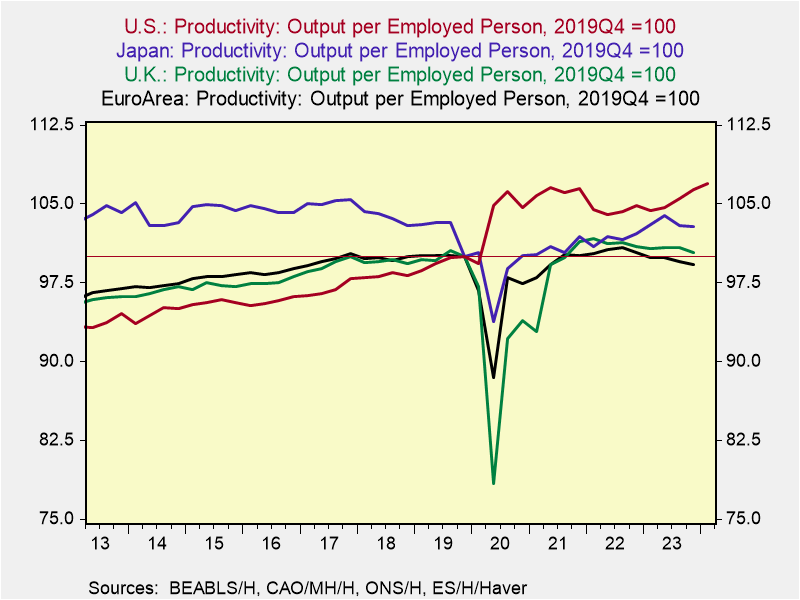

Associated with its stronger economic growth, productivity has strengthened in the U.S. Its average annualized gain in the three years before the pandemic was 1.7%, a marked increase from its annualized 0.7% gain in the prior six years, and has continued to rise at a healthy clip, although the aggregate data have been highly volatile, buffeted by large swings in employment in the low productivity services industries and the shift from full-time to pull-time work. Productivity gains have been healthy in Japan, but they have languished in Europe and the UK (Chart 8).

I estimate intermediate sustainable potential growth in the U.S. to be at least 2.25% far above the Fed’s current 1.8% estimate of longer-run sustainable growth. Higher real expected rates of return associated with higher productivity and potential growth are attracting foreign capital and supporting a stronger U.S. dollar.

Chart 8. International Comparisons of Labor Productivity

In contrast, productivity and growth have faltered in the EuroArea. Combined with unfavorable demographics affecting labor force growth, Europe’s outlook for sustainable potential growth has diminished, likely into the 0.75%-1.0% range. Of note, Germany had been Europe’s engine of economic growth, but that position began to erode before the pandemic, and in recent years, it has faced decided economic weakness and it lacks a viable strategy for its beleaguered automotive and energy-intensive industrial manufacturing sectors. Such potential growth is less than one-half of the U.S.’s. This is associated with a lower natural rate of interest and a weaker Euro.

A similarly soft productivity and growth pattern has unfolded in the UK, which has experienced a flattening of its labor force, despite a pickup in immigration. The IMF estimates UK potential growth to be 1.5%. Japan’s labor productivity of its working age population (age 16-65) is among the highest of all advanced nations. However, its healthy gains in productivity have been offset by weak demographics, marked by a declining and aging population that is reducing its labor force and low immigration, and traditionally Japan has not relied heavily on foreign workers.

The Outlook for Monetary Policy

The Fed has appropriately signaled that will delay any cut in rates. This is wise since inflation has backed up and interrupted disinflation while gains in employment and aggregate demand remain healthy. Of note, in Q1, nominal GDP rose 4.8% annualized and 5.5% yr/yr, consistent with sticky inflation, while real final sales to domestic purchasers (C+I) grew 3.1% annualized. Payroll growth slowed to 175,000 in April, but that pace of job gains is consistent with continued healthy growth in GDP, unless productivity slows abruptly, which seems unlikely.

The Fed remains fully data-dependent. Powell has stated that there is a very low probability that the Fed’s next rate move is up, and most Fed members await slower growth and a resumption of declining inflation they have projected so they can lower rates. (Whether the economic slowdown that seems to be unfolding is attributable to the Fed’s monetary tightening or merely a moderation from unsustainably fast growth is open to debate.) I continue to expect that will unfold and the Fed will begin cutting rates later this year.

However, the Fed has less room to lower rates. If the real neutral rate is 1.5%-2%, then eventually lowering rates to 3.5%-4% would be consistent with its 2% inflation target. In its latest Summary of Economic Statistics (SEPs), FOMC members estimated the longer-run fund funds rate to be 2.5%. The Fed tends to lag, and that estimate will rose very slowly.

The ECB has the most room to lower its policy rate, which is far above current inflation (Chart 6) while its neutral rate presumably has declined as its potential growth has diminished. Even though Europe’s economy is recovering from mild recession, it faces significant challenges. The ECB is expected to begin lowering rates mid-year 2024 and lower rates significantly through year-end 2025, and below 3% by mid-2026.

In the UK, even though inflation (4.6% headline and 3.7% core) remains far above the BoE’s 2% target, the BoE has signaled that it will begin cutting rates in June from its current 5.25% policy rate. The BoE’s decision revolves around two issues: first, the BoE places a high priority on maintaining the recovery from its recessionary conditions of 2023, and second, it expects inflation to fall significantly. This outlook is based on the BoE’s expectations that growth of aggregate demand will be weak, following its sharp deceleration in the second half of 2023, and the roll-off of the high monthly inflation data of 2023. But with inflation so high, providing forward guidance that it will be lowering rates is risky for the BoE.

The BoJ is gearing up to raise rates gradually and normalizing monetary policy to what it hopes is a new era of 2% inflation. Raising rates would also provide support for the battered yen, which is 155/USD after reaching 160/USD. Modest increases of interest rates toward 2% would elicit adjustments in financial markets. However, the BoJ’s sustained maintenance of a slightly negative policy interest rate since 2015 and expanded balance sheet had little apparent impact on real economic activity and inflation. As such, it seems unlikely that raising rates will have much effect.

The sequencing of these central bank policy changes will influence currencies. The yen is expected to strengthen. Monetary easing by the BoE and ECB before the Fed may keep the pound and Euro weak, although future markets have already begun to price in these changes. Once financial markets begin to anticipate that the Fed will lower rates, the US dollar is likely to weaken, but only modestly, in light of the outperformance of the U.S. economy and high expected rates of return on capital.

The Fed’s Strategic Approach to Monetary Policy Needs a Reboot

Fed Chair Powell has announced the Fed will conduct a strategic review of monetary policy later this year. This article, co-written by Mickey D. Levy and Charles I. Plosser, focuses on the characteristics and failures of the strategic framework that the Fed adopted in 2020 and how this framework contributed to monetary policy mistakes and high inflation. It provides suggestions on issues the Fed should consider in its upcoming strategic review.

The paper was presented at the Hoover Monetary Policy Conference, which took place on May 2-3.

In addition to Levy and Plosser, other presenters in the session were Athanasios Orphanides (MIT), Jon Steinsson (Berkeley) and Larry Summers (Harvard). John Cochrane (Hoover Institution, Stanford University) moderated.

Article: The Fed’s Strategic Approach to Monetary Policy Needs a Reboot

Slides: The Fed’s Strategic Approach to Monetary Policy Needs a Reboot

A Week of Insights into the Economy and Fed Interest Rate Policy

In an article published in the Wall Street Journal last Monday, I argued that there has been a pickup in productivity and sustainable potential real growth, which has raised the natural real rate of interest. These trends imply that the Fed’s real policy rate of 2.6% (the Fed’s current target of 5.25%-5.5% minus the 2.8% core PCE inflation) is not as restrictive as the Fed perceives, limiting the magnitude of interest rate cuts appropriate to achieve the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

The Fed’s view, as reflected in Fed Chair Powell’s testimony on the Fed’s semiannual Monetary Policy Report (MPR) to Congress, is that monetary policy is restrictive and will generate a significant slowdown in economic growth below potential that will lower inflation to 2%. Following this, important data releases throughout the week confirmed the continued health in labor markets and strength in household balance sheets that will support ongoing consumer spending. Later in the week, I also had the honor of discussing these issues with Larry Summers at an investment conference in Phoenix, Arizona. His views on the economy, real interest rates, and the Fed were similar with mine — and capped off a week full of insights.

WSJ Commentary. In my WSJ piece (“The Fed's Latest Problem: A Strong Economy,” March 4, 2024),

I fully understand the speculative nature of my assessment that productivity has picked up and the natural real rate of interest is higher than the Fed perceives. The productivity data bounce around a lot, and it’s too early to confirm any sustained pickup. The assessment of stronger productivity gains is based on mounting anecdotal evidence of rapid implementation of technological innovations such as generative AI, the efficiencies generated by heightened labor market mobility, the sizable shift in business investment toward software and R&D, and the big jump in new business formation. In addition, the natural real rate of interest is unobservable, and efforts to estimate it are iffy. Nevertheless, the assessment seems consistent with recent conditions in which real GDP has grown 3.1%, substantially faster than the Fed’s 1.8% estimate of sustainable potential real GDP growth, and the unemployment rate has been comfortably below the Fed’s estimate of a 4.1% natural rate of unemployment, despite the Fed funds rate at its higher level since before the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis.

Despite these caveats, my assessment is that the negative real Fed funds rate and low bond yields during the post-GFC expansion were the aberration, and interest rates have normalized. As shown in Chart I, the 1990s were characterized by high real interest rates, associated with a productivity boom and strong economic growth.

Important data. Labor market data remain healthy, with continued healthy increases in employment in February and the JOLTS data in January indicating softening demand for labor but generally tight conditions. Establishment payrolls rose 275,000 in February following the downwardly revised 229K in January, maintaining the 1.8% yr/yr rise in jobs. This is very healthy, by any measure. Aggregate hours worked in February rose 1.0%, more than offsetting the 0.6% decline in January. This will lift wage and salary and disposable personal income. The Household Survey, also released last week, was softer: On a positive note, the civilian labor force rose 150K, but employment fell 184K and unemployment rose 334K. There has been a noted divergence in the Household and Establishment surveys in recent months.

The JOLTS report for January registered modest declines in job openings and hires and a further modest decline in the quit rate, which combined indicated that while labor market demand continues to soften and close the gap with labor supply, labor markets remain healthy and relatively tight. These assessments were echoed in the Fed’s MPR and Powell’s testimony to Congress. Of note, the job opening ratio of 5.3% — total job openings as a percent of total employment plus job openings — remains well above its pre-pandemic level, while the hiring and quits rates are modestly below their pre-pandemic levels.

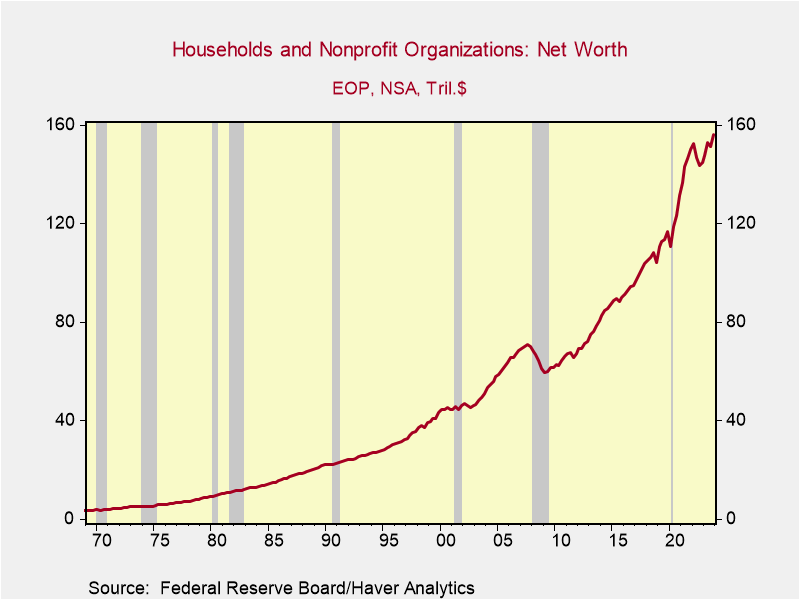

The Fed published its Financial Accounts of the United States for 2023Q4 Thursday, and the report was striking. Household net worth (net of all debt) increased $4.8 trillion in Q4, culminating a $11.6 trillion (8%) increase in the four quarters of 2023 (Chart 2). The stock of household net worth is 7.6 times the annual flow of national disposable personal income. Of the total household net worth, $31.8 trillion, or only 20.3%, is owner equity in real estate. While this huge magnitude of wealth is unevenly distributed, a sizable number of households have a significant amount of net worth that is flowing into the economy and raising the propensity to spend (“Consumption and Household Net Worth,” December 21, 2023). As I note below, it’s no wonder consumers are spending and the rate of personal saving relative to disposable personal income is low.

The Fed’s Monetary Policy Report and Powell’s Congressional Testimony. The Fed’s thorough report described evidence of healthy economic growth, tight labor markets, and the favorably lower inflation trend. Powell echoed these themes in testimony and underlined the Fed’s goal of reducing inflation to 2%. Consistent with recent public statements, Powell characterized monetary policy as restrictive, presumably reflecting the high real Fed funds rate, that the Fed projects will slow real GDP growth to 1.4% in 2024 (Q4/Q4) and thereby lower inflation to 2%.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Fed’s MPR is the report on “Monetary Policy Rules in the Current Environment” that appears at the end of Part 2 on Monetary Policy. It describes equations for the Taylor Rule and four other interest rate rules for conducting and assessing monetary policy. In keeping with the Fed’s heavy reliance on discretion, the report discusses the limitations of using simple rules for the conduct of policy but does not describe how using the Taylor Rule or other rules would have resulted in better monetary policy and economic outcomes. The concluding chart of historical federal funds rate prescriptions from the simple policy rules shows how the Fed was way behind in raising rates in 2021-2022 relative to the rules’ prescriptions, and how the Fed funds rate currently is very close to the prescribed rules. This observation seems consistent with my assessment that the natural real rate is higher than the Fed perceives which reduces the magnitude of room to lower rates.

An Educational Investment Conference. On Thursday, I participated in an investment conference in Phoenix, Arizona attended by 200+ people involved in investments and sponsored by Smead Capital Management and others. In the first session, I was honored to share the stage with Larry Summers in a discussion about economic conditions and the Fed.

In response to an opening question about the economy, Summers was positive, and tackled head on the Fed’s surprising resilience in the face of its aggressive rate increases. He detailed how all of the conditions upon which he had based his 2016 secular stagnation hypothesis (“The Age of Secular Stagnation: What It is and What to Do About It,” 2016) — insufficient demand, excess saving, low natural interest rates, as originally hypothesized by Alvin Hanson in the 1930s and subsequently used by Bernanke (2003) and more recently to explain the anemic recovery from the Financial Crisis by Ken Rogoff, Robert Gordon, and Paul Krugman, all of whom argued the need for more government fiscal stimulus to boost demand) — have reversed.

Summers agreed with me on the pickup in productivity and sustainable growth, citing anecdotal evidence of technological innovations efficiencies that were transforming the economy, and argued that natural rate of interest was “somewhere between 4% and 4.5% rather than Fed’s estimate of 2.5% [he added inflation]...so it’s no wonder that the Fed’s aggressive rate increases haven’t slowed the economy.” He stated that it's not that his secular stagnation hypothesis was wrong; rather, he quoted Keynes "When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?"

In response to Summer's discussion of secular stagnation, I noted that much of the anemic recovery from the Financial Crisis (marked by high saving rates and insufficient demand) and low inflation reflected household efforts to replenish their balance sheets that had been severely damaged by the collapse in home values and household net worth during the GFC and the unwise buildup of $1.4 trillion in home equity loans. I juxtaposed those dire conditions with the current relative healthy household balance sheets and soaring household net worth. It should be no surprise that the current rate of personal saving is well below the rates that persisted following the Financial Crisis, and that growth in aggregate demand is healthy. My assessment, which requires further empirical research, has far-reaching implications for the sources of the anemic recovery and low inflation that followed the Financial Crisis, which influenced the Fed’s thinking about inflation and its policies in response to the pandemic.

Summers continued to say that while he thought the government data over-stated inflation when it was high in 2021-2022, the data now are understating the underlying inflation pressures. He also expressed serious concerns about the persistent government deficits and debt, and projected higher bond yields.

The next panel at the investment conference involved a very interesting discussion of venture capitalists. As they detailed the role of VCs, the panelists brought to life how technological innovations are transforming activities and businesses in an array of industries and how risky capital was financing innovations and research. My clear walkaway is that even if the economy slows cyclically, the pace of technological innovations and implementation into commerce will continue to speed ahead.

Chart I. The Fed Funds Rate and Core PCE Inflation

Chart 2. Household Net Worth

Time for Fed to Recalibrate View of What's Restrictive?

Here is an interview with Kathleen Hays on her podcast, Central Bank Central. It is based on Levy's Wall Street Journal opinion piece, "The Fed's Latest Problem: A Strong Economy." The discussion sets the stage for assessing the upcoming Fed semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress and the March 19-20 FOMC meeting in which the Fed will provide its updated Summary of Economic Projections.

U.S. GDP, Profits, and the Stock Market

The U.S. stock market continues to outperform leading overseas markets, reflecting stronger economic growth and the rise in profits, and the expectations that these innovation and technology-drive trends will continue. In anticipation of this Thursday’s GDP Report, which is expected to record another healthy gain in U.S. GDP in 2023Q4, this brief assesses the longer-run trend in the U.S. economy and profits and highlights some important evolving trends.

International comparisons of stocks, profits and GDP

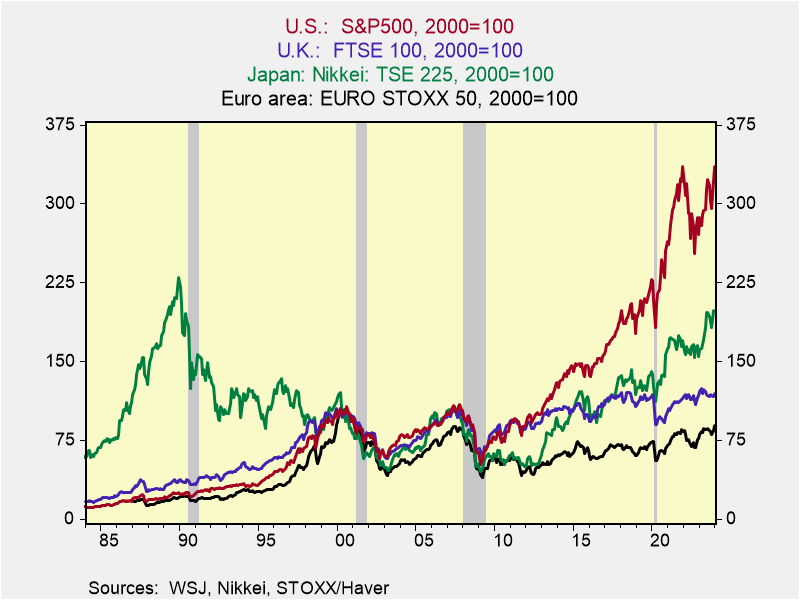

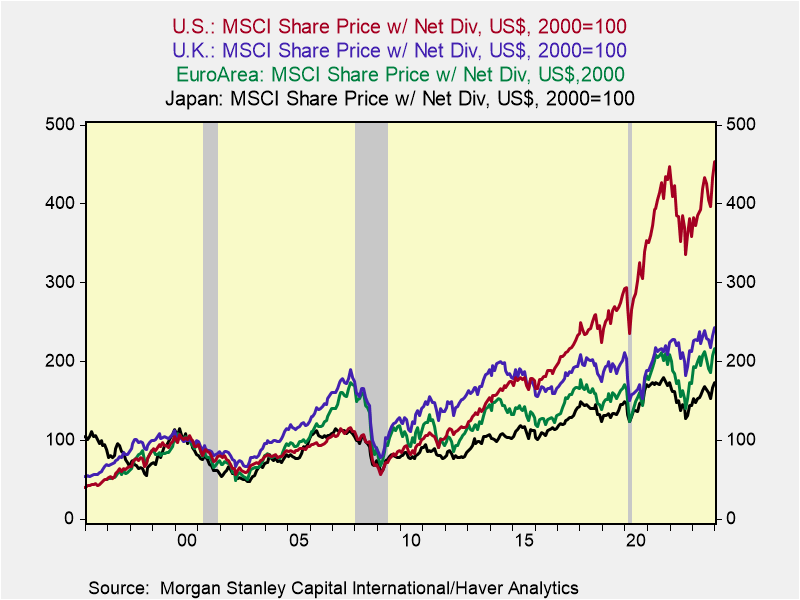

Chart 1 shows the cumulative appreciation of the S&P500 indexed to 2000 compared with the stock market performance of Japan’s Nikkei, the EuroArea EUROSTOXX, and the UK’s FTSE. The cumulative outperformance of the U.S. stock market, particularly since 2015, is striking. Chart 2 shows that comparing the stock indexes, including net dividends and measured in US dollar terms, provides similar results (Chart 2).

Chart 1. International Stock Indexes Chart 2. Stocks with Dividends

In US$

These stock returns mirror the relative outperformance of the U.S. economy and profits. Chart 3 shows the cumulative growth of real GDP since 2000 in the U.S., Japan, Europe, and the UK. The gap reflects the U.S.’s combination of faster gains in productivity and labor force. The U.S.’s pace of growth has decelerated over time, reflecting a combination of slower gains in labor force and productivity. Japan’s economic growth has been constrained by declining population and labor force; these trends have offset Japan’s highly productive workforce. Europe’s economy was harmed by financial crisis and has been constrained by overbearing regulations and high taxes and it faces major structural problems. The UK’s economy has been saddled by uncertainty stemming from swings in leadership and lack of a coherent economic growth strategy.

Chart 3. International Comparisons of Real GDP

Estimates of U.S. potential growth have diminished over time: Estimates by the Federal Reserve and the Congressional Budget Office center on 1.8%. I am more optimistic about potential growth, based on an anticipated pickup in productivity gains driven by the U.S.’s world-leading innovations and entrepreneurship, and increases in the labor force that will be driven, in part, by increased immigration. Even with Japan’s healthy productivity, its diminished labor force has constrained its potential growth to an estimated 0.5%. Europe’s potential growth is now decidedly below 1%, with a wide variance across its nations. While growth prospects in Spain and southern EU nations have improved, Germany, Europe’s largest economy and its engine of growth though roughly 2017, has faltered badly, faces significant structural problems, and is now a drag on Europe’s economy overall. The UK’s potential is modestly below the U.S.’s but suffers from a lack of policy stability and purpose that undercuts confidence.

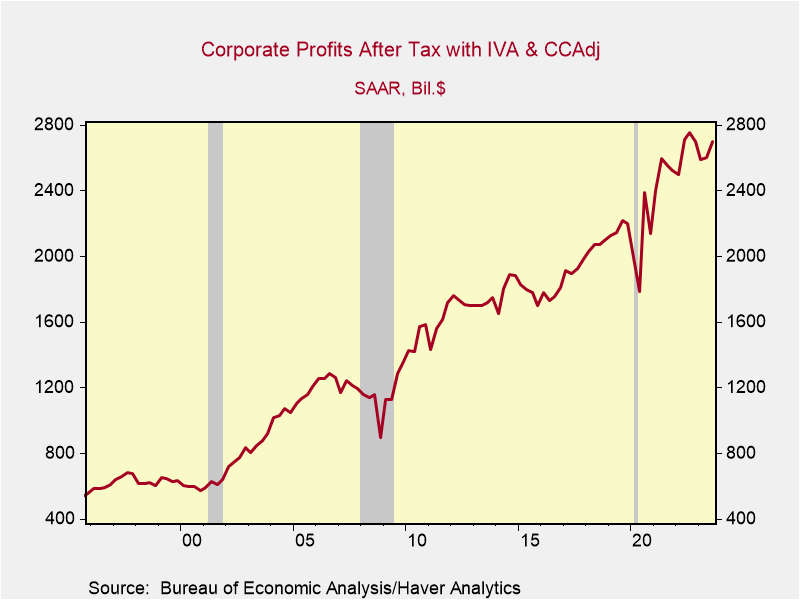

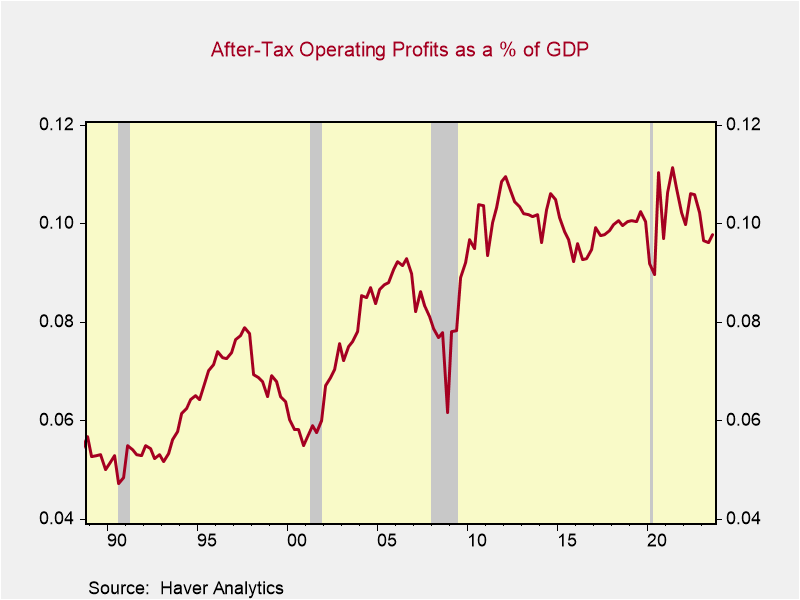

Comparisons across nations more problematic since the UK and EuroArea do not maintain data comparable to the U.S. or Japan. Chart 4 shows U.S. operating profits adjusted for inventory valuation and capital consumption allowances, indexed to 2000. Chart 5 shows after tax corporate operating profits as a percentage of GDP. They are high in historic terms but within their recent 10-year range. Based on corporate and profit data for S&P500 companies, U.S. profit growth is presumed to exceed those generated overseas. Of note, U.S. multi-national corporations generate repatriated profits from overseas activities that do not add to GDP, boosting the elasticity of profits relative to GDP. Presumably, Europe’s profits lag far behind, reflecting its slower economic growth, higher taxes and onerous regulations.

These relative trends in GDP, profits and stock markets, and the factors that drive them are embedded in expectations. Such high expectations reflect the optimism that the U.S.’s dominance in innovation and technological innovations and effective implementation into commerce will continue. They support the U.S.’s relatively high stock market valuations, independently of the discount rate of the future steam

Chart 4. U.S. Operating Profits Chart 5. Profits as a % of GDP

of earnings. Certainly, there are periods of outperformance of stocks in Japan, Europe, and the UK, but convergence of their stock price multiples with the U.S. should not be expected unless there is a convergence of expectations of economic growth or profits.

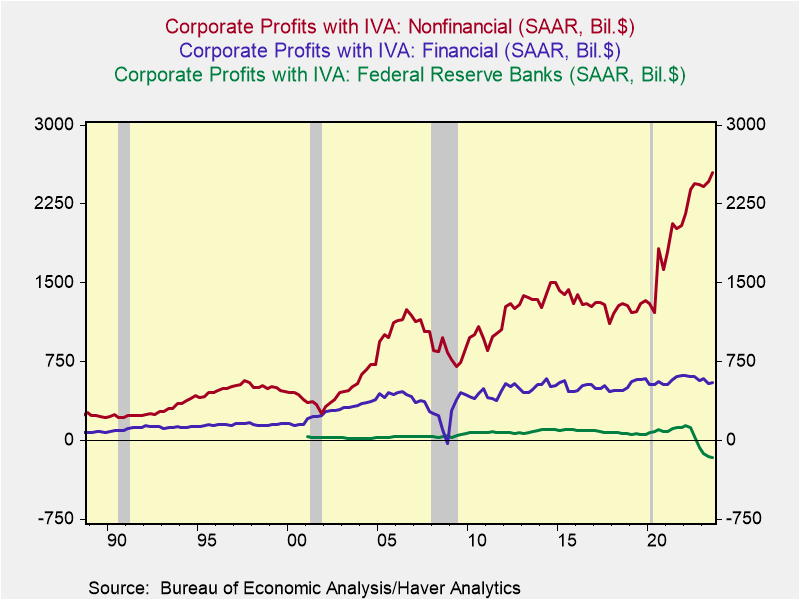

Profits in U.S. domestic industries have dominated net profits from overseas activities. The latter account for approximately one-sixth of total profits. Profits of U.S. nonfinancial industries have risen sharply since the pandemic, while profits in the private domestic financial sector have risen modestly. As shown in Chart 6, the Federal Reserve is now

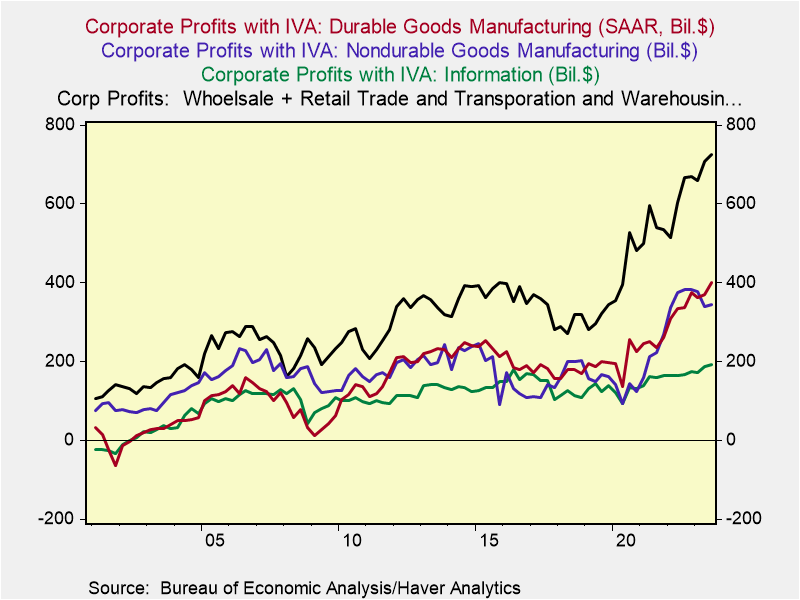

Chart 6. Trends in Corporate Profits Chart 7. Trends in Nonfinancial Profits

losing money, reflecting the adverse impact of higher interest rates on its bloated portfolio resulting from its massive asset purchases. Chart 7 shows the distribution of healthy profit gains across most nonfinancial industries. Profit gains in durable and nondurable goods manufacturing have been particularly strong since the pandemic.

Trends in U.S. GDP

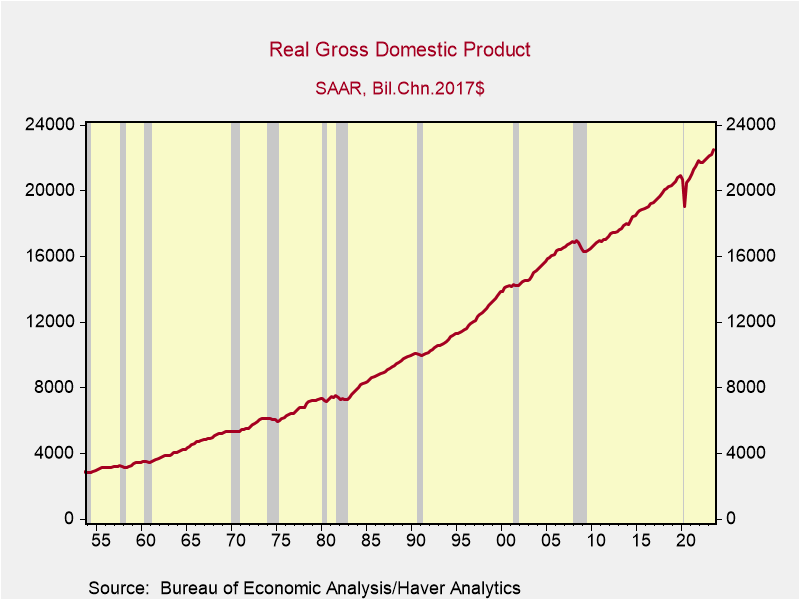

The longer-run trend of real GDP highlights its nearly persistent rise that is periodically interrupted by recession that with only a few exceptions — the mid-1970s, the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, and the 2020 pandemic — seem rather minor (Chart 8). Of course, quarterly and yr/yr changes are much choppier and reveal the cyclical fluctuations in GDP that dominate financial market analysis and media coverage. But it’s the longer-term upward trend in real GDP that is the primary driver of economic progress and higher standards of living.

Chart 8. Longer-run Trend in Real GDP

Among the components of real GDP, several trends stand out. Consumption remains roughly 68% of GDP, close to a high, reflecting the rise in consumption of goods as a

percent of GDP and the modestly declining share of consumption of services. Goods consumption has been driven by spending on recreational goods and vehicles, particularly since the pandemic. The share of nondurables consumption has diminished over time, but has jumped since the pandemic. The declining share of consumption of services as a percent of GDP reflects falling real spending on financial services and insurance, reflecting narrower margins, along with flatter real consumption of housing and utilities.

Most strikingly, the share of nonresidential investment has risen dramatically — climbing to 14.5% from 9% in the 1990s and 12% during the 2010-2019 expansion. This reflects the surge in business investment spending on software and R&D. During the same period, investment in structures and industrial equipment has lagged the growth in real GDP. As described in earlier reports, the dramatic rise in business spending on software and R&D has been at the center of the innovation- and technology-driven growth of the economy, and has also served to dampen the cyclicality of the economy (Factors Supporting a Soft-Landing, December 10, 2023).

Residential investment, which includes new home construction and home improvements, peaked at 6.9% during the debt-financed housing bubble in 2007 and has diminished to 3.3%.

Exports have declined to 11.1% of real GDP, a modest decline from their average in 2010-2019, while imports have continued their rise, climbing to 15.2%. This has resulted in a widening of the real trade deficit to 4.1% of GDP, reflecting the extent to which domestic demand exceeds domestic production — and a widening current account deficit.

Government purchases — consumption and investment — that directly absorb national resources and are counted in GDP have gradually diminished over time, and now stand at 17.1%, down from 25% in the 1980s. At the same time, government deficit spending has continued to rise, reflecting the compounding increases in transfer payments, largely entitlement programs that provide income support. This involves the ongoing shift in the direction and purpose of government spending, allocating more resources toward income support and redistribution.

The biggest swing factor in government purchases as a percent of real GDP has been spending on national defense, which declined sharply in the 1990s from 7% of GDP to 4% and has drifted down to its current 3.7%. The recent increases in government investment in infrastructure spending on defense has contributed to real GDP growth (Fiscal Policy and the Fed Work at Cross Purposes, September 9, 2023).

Real GDP and its components convey critical information about trends in the economy and business environment. The upcoming GDP Report for 2023Q4 will not disappoint.

Trends Influencing 2024’s Economic and Political Landscape

Trends Influencing 2024’s Economic and Political Landscape

Along with the health of the U.S. consumer, four economic trends at the forefront of the political economy — the flattening of international trade, China’s economic slump, the decline in inflation amid continued rise in consumer prices, and the U.S. housing market — will influence the economic and political landscape in 2024.

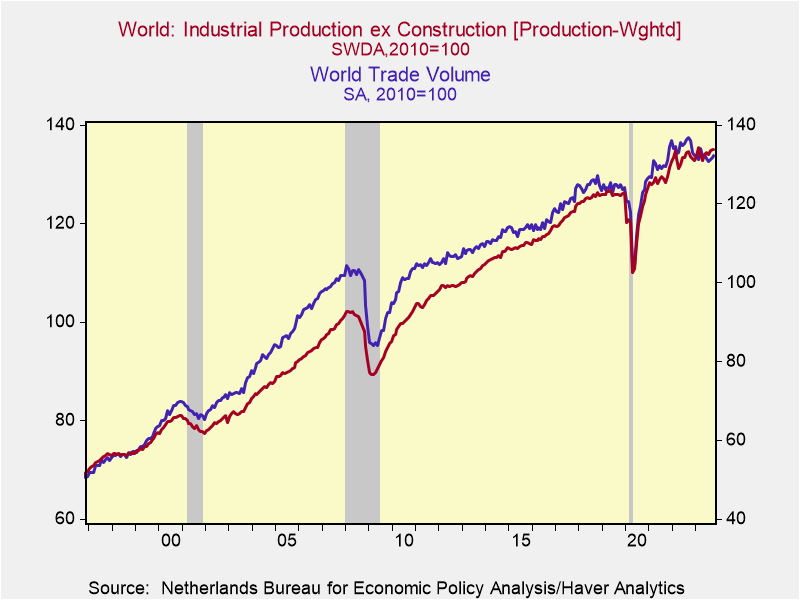

International trade. Global trade volumes have flattened, as nations are retreating into regional shells (including a rapidly growing trading bloc centered around China, Russia and Iran), global corporations are restructuring their supply chains (away from China) and facing higher costs of financing trade and global supply chains, and physical trade is being inhibited and threatened by military and terrorist attack. These trends are a negative for global growth and efficiencies (Chart 1).

Chart 1. Global Trade and Industrial Production

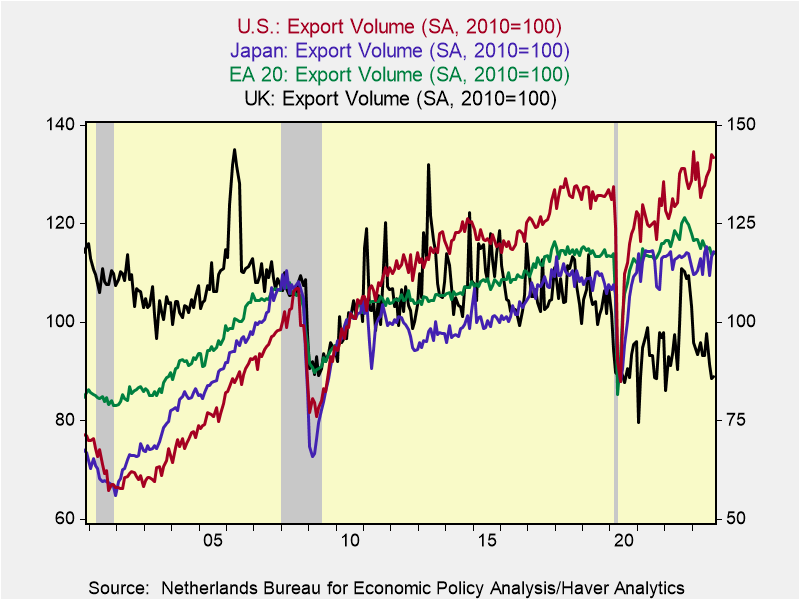

So far, the biggest brunt on international trade has been felt by the United Kingdom and Europe, where exports and imports are down significantly since before the pandemic. Japan has also been adversely affected by its large trade exposure with China. The U.S. is better situated (Chart 2): although it has smaller relative export exposure than the UK, Europe, Japan and other advanced economies as a percent of GDP, its exports have continued to grow. Fortunately, its two largest trading partners — Mexico and

Chart 2. International Comparisons of Exports

Canada — are also relatively insulated from China’s economic weakness and continue to grow. Mexico (and, to a lesser extent, other Latin American nations, including Brazil) is well positioned to benefit as it becomes an attractive center for production for global companies.

Nevertheless, the unwind and restructuring of global supply chains away from China is costly in terms of efficiency, and in the short run imposes economic costs that exceed any benefits stemming from onshoring of production and jobs. As James Manyika and Michael Spence state in “The Coming AI Economic Revolution” (Foreign Affairs, November/December 2023): “The era of building global supply chains entirely on the basis of efficiency and comparative advantage has clearly come to a close.” Moreover, the distortions and geopolitical risks stemming from the Russia-Ukraine war and war in the Middle East are raising the costs of trade and suppressing international trade, at least temporarily. Moreover, a concern looms: the weakness and disruptions to international trade may be significantly accentuated if Donald Trump were to be elected president and impose tariffs and barriers to trade, as he has promised to do.

China. China’s deflation — its yr/yr consumer price index has fallen for three consecutive months — is a direct consequence of insufficient aggregate demand and economic slump. Don’t look for any positive economic turnaround in 2024 in China, and take the official data published by China’s National Bureau of Statistics with a big grain of salt. The Chinese government is trying to stabilize home values and expectations, lift confidence, and encourage consumer spending. China’s official data put real GDP growth at 5% but a more realistic assessment is closer to 1½% (see Rhodium Group, “Through the Looking Glass: China’s 2023 GDP and the Year Ahead”, December 29, 2023). Such growth is not sufficient to maintain employment and wages. The deflation adds to the lack of confidence and social unrest, particularly among China’s youth that must adjust down expectations about their future. That’s the cost of a Communist dictatorship.

As described in earlier papers (“China’s Bill Comes Due,” September 19, 2023), President Xi’s clampdown on U.S.-style free enterprise has undercut innovation and productivity while the gross misallocations of resources that culminated in unsustainable excesses in real estate as Chinese leaders attempted to maintain unrealistically high levels of GDP growth have unraveled. The collapse in the government-generated excesses in real estate has generated sizable losses in household net worth and generated a sizable hole in local government finances. The former has dampened consumer spending while the latter has severely undercut local government finances and constrained China’s ability to finance fiscal stimulus. Similar with Japan’s asset price bubble in the late 1980s and the U.S.’s debt-financed housing bubble in the early 2000s, the adverse consequences for China’s consumers and domestic demand will be felt for years.

At the same time, global demand for China’s goods and production have been slowed by economic weakness in Europe and the UK and select emerging nations, along with efforts of global companies and advanced nations to reduce supply chain exposure to China. This reduces jobs in China’s export-related manufacturing industries. These negatives have been mitigated by China’s booming production and exports of EVs and strong gains in exports to Russia, Iran and the Middle East. The building of this new axis of trade has been a distinct positive for China, but not nearly enough to offset the weakness in trade with advanced economies.

In summary, China is no longer the engine of global growth and world economies must adjust.

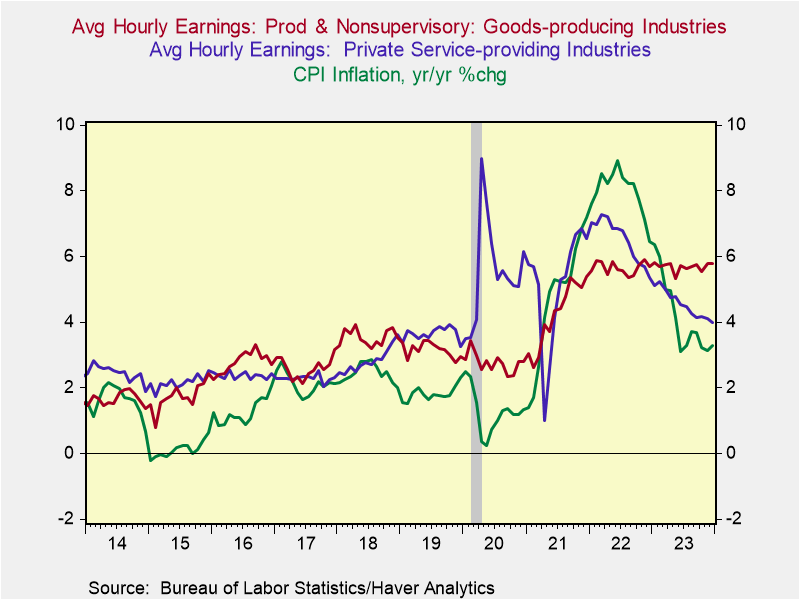

Disinflation but higher prices. The decline in inflation — measured yr/yr, CPI inflation has receded to 3.3% and 4.0% excluding food and energy (3.3% and 3.2% annualized in the last six months) — has resulted in an increase in real (inflation-adjusted) wages and purchasing power. Real average hourly earnings rose 1.0% in the year ending December 2023, retracing one-half of the decline in 2021-2022. And recent declines in energy prices have boosted purchasing power (Chart 3).

Chart 3. Average Hourly Earnings and Inflation

The lower inflation is a distinct positive for consumers and economic performance. On the other hand, prices of goods and services continue to rise, and following the 2021-2023 surge in inflation, they are dramatically higher than pre-pandemic levels. These price increases have impinged on standards of living for households and the price sticker shock is resonating in election year politics.

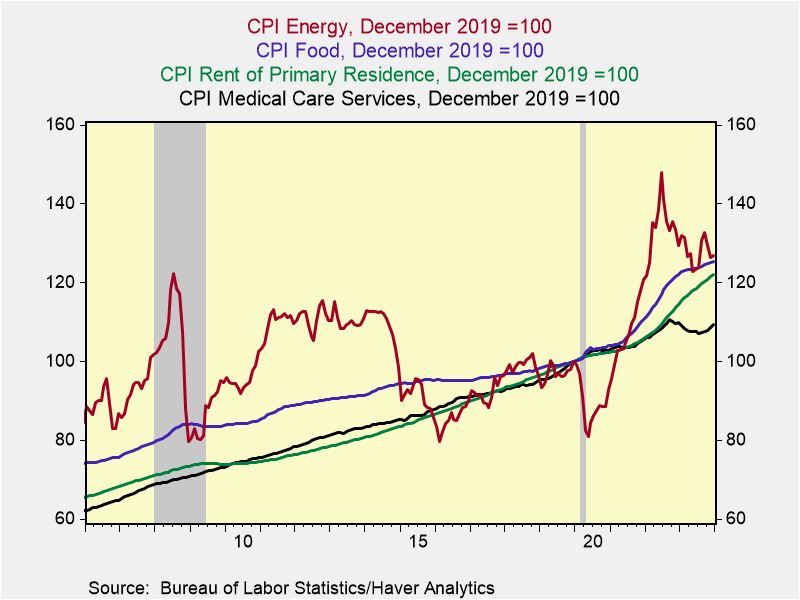

Since before the pandemic (December 2019), prices of food have risen 25.4%, rental costs are up 21.9% and even with the simmering down of energy costs, energy prices are up 26.9%. Of note, the large laggard in price increases has been health care costs that are up only 9.3% since late 2019 (Chart 4). One factor underlying this subdued price increase may be the government’s efforts to constrain budget outlays for Medicare, Medicaid, and other subsidized health care that has involved squeezing reimbursable schedules. This would affect the price changes recorded for an array of medical care services. (Note the CPI measures price changes of out-of-pocket consumer expenditures, while PCE inflation measures price changes of total consumer expenditures including those paid for by Medicare, Medicaid and corporate health care insurance.)

Chart 4. Price Increases since Before the Pandemic

The Fed’s stated mandate is 2% average longer-run inflation, and the objective of its strategic plan is to let bygones be bygones, with no intention of a makeup strategy that would offset the 2021-2022 surge in inflation.

The higher prices are having the largest impact on lower- and middle-income households who are renters and face dramatically higher costs of living but have not benefited from home ownership or the stock market appreciation. The resulting impacts on real incomes and wealth of households with different social and demographic characteristics may influence perceptions and affect election outcomes.

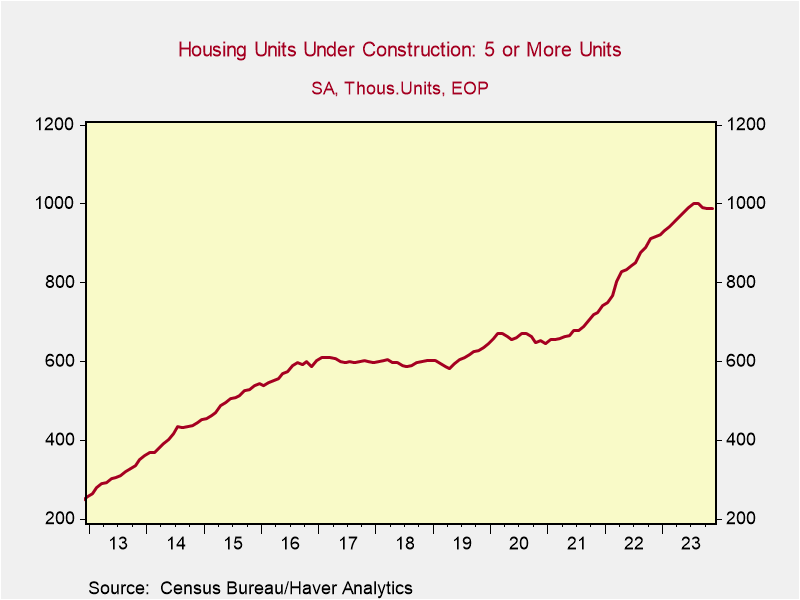

U.S. Housing. New and existing home sales and construction have been constrained by insufficient supply and the sharp rise in mortgage rates through October 2023. The constraints on supply of existing homes stemming from low mortgage rate lock-ins has only compounded the shortfall in the housing stock that accumulated during the 2010-2019 expansion when new unit construction was persistently below the growth in demand associated with new family formation. These imbalances have contributed to stubbornly high home prices and decades-low home affordability index. Meanwhile, healthy labor mobility continues to support housing demand in medium and smaller-sized cities.

Relief may be coming: the recent sizable decline in mortgage rates has improved home affordability and will increase demand, and, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of completions of apartments that will come on the market in 2024 will be 50% higher than the record-breaking 444,000 in 2023 (Chart 5). These increases in supply and demand along with lower mortgage rates are expected to increase sales while providing some relief on prices. Not surprisingly, contractors are expecting a strong homebuilding season in Spring 2024.

Chart 5. Multi-Family Housing Units under Construction

As described in recent briefs, these positive factors of disinflation and housing are expected to support continued economic expansion in the U.S., while the impacts stemming from constraints on international trade and China’s ongoing economic woes are negatives and require scrutiny.