Keep an Eye on Real Wages and Hours Worked in Economy

U.S. economic growth has remained solid through most of 2025, driven by healthy gains in consumption and strong business fixed investment, particularly for the buildout of AI. This has defied the pessimists’ worries about President Trump’s misguided tariffs, clampdown on immigration and cuts in research grants to universities. The only real laggard in 2025 was the housing sector, which suffered from continuous declines in spending on construction and improvements. But that was last year and we should not expect any let up in erratic tariff policies and anti-immigrant initiatives in 2026.

Despite these obstacles, the outlook for sustained expansion in 2026 looks favorable, and the probability for recession is low. Current conditions are inconsistent with onsets of recession in the past. Consider the following two items that will support aggregate demand: 1) three Fed interest rate cuts in September-December 2025 lowered the real Fed funds rate below the Fed’s estimate of the longer-run real rate of interest consistent with its dual mandate of 2% inflation and maximum employment, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s Financial Conditions Index signals loose financial conditions, and 2) fiscal policy is stimulative, as the OBBBA of 2025 extended the 2017 tax cuts and added some additional cuts (eliminating tax on income from tips, expensing of outlays for research and development) that will boost tax refunds in Spring 2026 by approximately 0.6% of disposable personal income. In this environment, 3) business inventories are relatively low and 4) employment is well-aligned with output (GDP). Accordingly, any slump in aggregate demand will not force businesses to cut output and/or employment in a meaningful way.

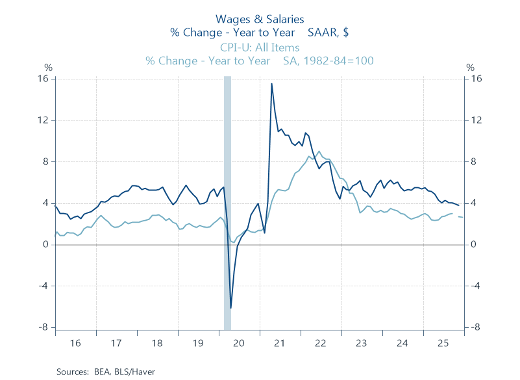

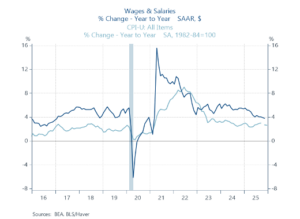

Labor market and personal income dynamics. One key trend to keep an eye on is real wage and salary incomes, a key indicator of labor market conditions and measure of consumer purchasing power. Growth in personal income from wages and salaries has decelerated to 3.8% in the year ending November 2025 (Chart 1). That’s down from a 5.5% rise in the prior year. At the same time, CPI inflation was 2.7% in the last two years ending November 2025. According, the year-over-year growth in real personal disposable income from wage and salaries has receded to 1.1% in the year ending November 2025, significantly slower than its 2.8% rise in the prior year.

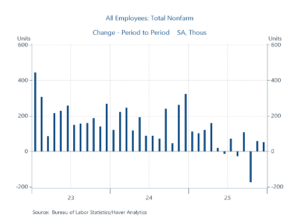

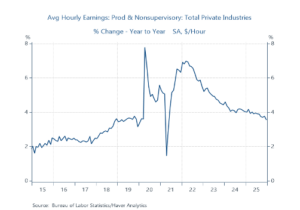

This deceleration in real wages and salaries reflects primarily a combination of moderating gains in average hourly earnings (AHE) and weakness in employment. As shown in Chart 2, AHE have moderated to 3.5% year-over-year growth from 4.1% a year earlier. The yr/yr rise in AHE will decline further in the January and February 2026 readings as the high monthly increases in Jan-Feb 2025 roll off. At the same time, establishment payroll gains have flattened significantly. In the six months July-December 2025, employment rose a net 87,000, an average of 14k per month; in the prior six months jobs rose 497k, an average monthly rise of 82k (Chart 3). In the prior year ending December 2024, employment rose over 2 million.

Chart 1. Wages and Salaries and CPI Inflation

Chart 2. Average Hourly Earnings

Chart 3. Establishment Payrolls

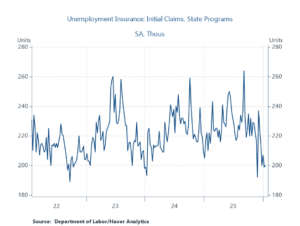

The flatter employment gains and weakening of labor markets is a product of less supply of labor and weaker demand. Trump’s clampdown on immigration has clearly constrained the supply of labor. It has probably also dampened business demand for labor, particularly in construction and leisure and hospitality sectors. Businesses have responded by slowing hiring while the high costs of search and hiring have reduced their layoffs. Initial unemployment claims have remained low (Chart 4).

Chart 4. Initial Unemployment Claims

Amid slower gains in employment and average hourly earnings, the positive in labor markets is aggregate hours worked increased 0.7% in 2025. That’s fortunate insofar as wages and salaries and disposable personal income are driven by hours worked, not employment. Importantly, stronger productivity gains have powered the solid economic growth. During the year ending 2025Q3, productivity (private output/aggregate hours worked) in the nonfarm business sector rose 1.9% and 2.3% in the manufacturing sectors. This decided pickup in productivity reflects the continued momentum in business investment in data storage and related AI infrastructure plus production efficiencies stemming from broadening uses of AI innovations in both manufacturing and service-producing industries.

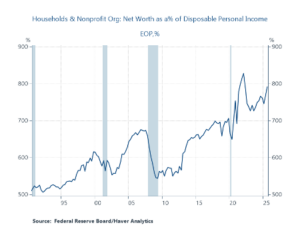

The wealth effect and rate of personal saving. Most households spend most of what they earn, so consumption will be driven largely by growth in disposable income. In addition, the ongoing surge in household net worth, reflecting the rise in equity valuations and real estate, has lifted the propensity to spend. In the last year, household net worth has risen 7.6% to an all-time high of $181 trillion. To put it into perspective, household net worth has risen to 7.9 times the annual flow of disposable personal income (Chart 5). The sharp increases in household net worth are adding to the flow of disposable income (through required minimum withdrawals of IRAs and private pensions and gifting and the like) and boosting consumption through the positive wealth effect--increasing the propensity to spend out of disposable income. As a result of the sizable wealth effect, the rate of personal saving declined to 3.5% at its last reading in November 2025. It cannot be expected to fall much further.

Chart 5. Household Net Worth/Disposable Personal Income

Add it all up, and consumer purchasing power, driven by employment, hours worked and average hourly earnings, are key variables to follow in 2026. The highest probability outlook is continued expansion at a slower pace of growth.

Mickey D. Levy is a Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and a longstanding member of the Shadow Open Market Committee

Monetary Policy Responses to Shocks

Here's a paper and presentation that I co-authored with Dr. Michael Bordo and presented at the November 2025 Shadow Open Market Committee meeting. "Monetary Policy Responses to Shocks" analyzes the history of shocks — the Great Inflation of 1965-1982, the Great Financial Crisis and Covid, plus an array of minor disturbances — and how the Fed responds to them. We find that the Fed has responded unsystematically, and often in ways that extend and accentuate the costs imposed by the original shock.

Paper: Monetary Policy Responses to Shocks (Michael D. Bordo and Mickey D. Levy, Nov. 7, 2025, Shadow Open Market Committee)

Power Point: Monetary Policy Responses to Shocks (Michael D. Bordo and Mickey D. Levy, Nov. 7, 2025, Shadow Open Market Committee)

The SOMC meeting, the first in its partnership with the Center for Financial Stability, included great presentations on Fed independence, Fannie and Freddie, and financial stresses.

Reflections on Jay Powell’s Jackson Hole Speech

Jay Powell’s Jackson Hole speech covered two topics: a review of current economic and inflation conditions and the stance of monetary policy, and an outline of the Fed’s new Strategic Plan and how it has been revised from its 2020 Strategic Plan. In summary, Powell’s assessment of current conditions tilted toward expressing more concern about labor market weakness than above-2% inflation, fueling expectations of Fed easing, while the Fed’s revised Strategic Plan eliminated some of the key asymmetries in its 2020 Strategic Plan that favored higher inflation and prioritized maximum employment, reverting more closely to its balanced 2012 Consensus statement.

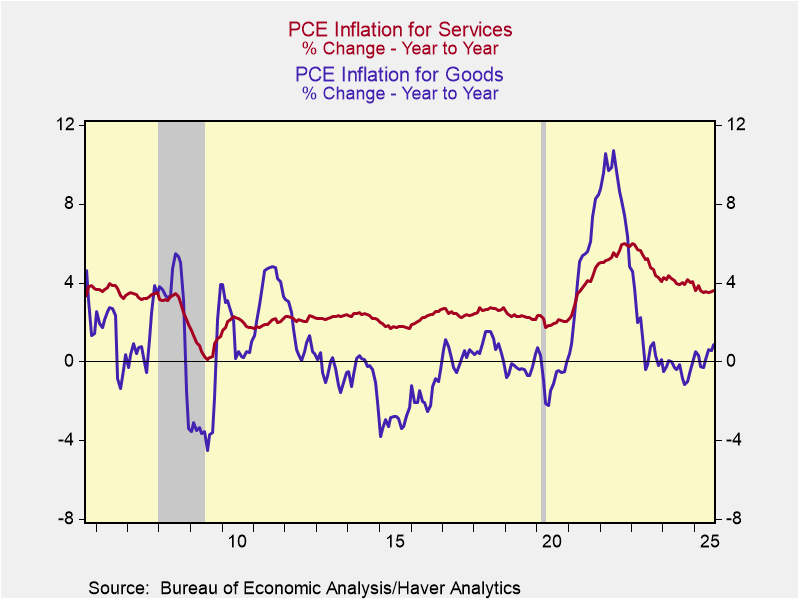

The Fed’s economic review and policy stance. Powell’s assessment of the economy is that tariffs, immigration policies and related uncertainties have weighed on performance and slowed growth and weakened labor markets, and that inflation has remained elevated, and the impact of tariffs on consumer prices has become more visible. He stated that while inflation has remained above the Fed’s 2% target for 4 years, both survey and market-based measures of inflationary expectations have remained anchored to the Fed’s 2% long-run inflation target. He concluded that “…with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the shifting balance of risks may warrant adjusting our policy stance”.

While carefully crafted, his statement suggests that the Fed is accepting of inflation modestly above its 2% target because it views current monetary policy as restrictive, which will weaken economic growth and eventually lower inflation, and the Fed is concerned about weakening labor markets. The Fed’s perception that monetary policy is restrictive is based on its observation that the real (inflation-adjusted) Fed funds rate target (4.25%-4.5%) is comfortably above the FOMC members’ estimate (in the Fed’s June 2025 Summary of Economic Projections) that the longer-run r* (the natural real rate of interest consistent with the economy growing along its potential path and the Fed’s 2% inflation target) is 1%. My view is r* is higher, which suggests that monetary policy is not as restrictive as the Fed perceives.

Financial markets picked up this tilt, as Treasury bond yields fell, the stock market rose and the US dollar fell.

The Fed’s revised Strategic Plan. Based on its obsession with the Effective Lower Bound, driven by its worries about too-low inflation and risks of a collapse in inflationary expectations combined with its view of a persistently low real interest rates, the Fed’s 2020 Strategic Plan introduced asymmetries into its 2012 Consensus Statement, advocating above-2% inflation for an undefined period of time as a “makeup strategy” following a period of below-2% inflation (through its “Flexible Average Inflation Targeting”; there was no make up strategy following an above-2% period of inflation), prioritizing its employment mandate (by replacing the word “deviations” with “shortfalls” from maximum employment), and effectively eschewing preemptive monetary tightening when full employment anticipated higher inflation.

The newly revised 2025 Strategic Plan reverses those asymmetries: it “removed language indicating that the ELB was a defining feature of the economic landscape”, removed the “makeup strategy” favoring higher inflation following periods of below-2% inflation, re-emphasized that “price stability is essential for a sound and stable economy and supports the well-being of all Americans”, dropped the use of “shortfalls” from maximum employment, and in a back-handed way reinstituted pre-emptive monetary tightening (“In particular, the use of ‘shortfalls’ was not intended as a commitment to permanently forswear preemption or to ignore labor market tightness”). The Fed also stated that “consistent with the removal of ‘shortfalls’, we made changes to clarify our approach in periods when our employment and inflation objectives are not complementary”.

While Powell avoided directly criticizing the 2020 Strategic Plan, the Fed’s explicit reversal of the asymmetries that the 2020 Plan had introduced was clear. Powell stated “In approaching this year’s review, a key objective has been to make sure that our framework is suitable across a broad range of economic conditions.” Of course, that’s a key characteristic of a robust strategy. In reality, the 2002 Strategic Plan was more of a tactical plan that allowed the Fed to overheat the economy and allow higher inflation because of its overstated fears of too-low inflation and the ELB. Powell concluded his remarks by emphasizing that the newly revised Strategic Plan is consistent with the Congressional mandate of price stability and maximum employment.

A note in remembrance of Charlie Plosser. When Charlie was President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, with the urging and 100% support of Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, Charlie was a key architect of the Fed’s original Strategic Plan in 2012 that established its dual mandate of a 2% inflation target and maximum employment, while noting that a numeric target for employment was inappropriate because labor markets are affected by many non-monetary factors that are beyond the control of the Fed’s monetary policy. Charlie always emphasized the benefits of the symmetry of the Consensus Statement’s dual mandate and how it was robust under different circumstances, was easy to understand and facilitated clear communications. Immediately following Jay Powell’s roll out of the Fed’s 2020 Strategic Plan in his Jackson Hole speech in August 2020, Charlie and I teamed up and wrote a critique that identified all of the flaws and asymmetries of the Fed’s new Strategic Plan and concluded that it would only be a matter of time before its flaws would be revealed (The Murky Future of Monetary Policy, October 1, 2020, Hoover Institution Working Paper). Subsequently, inflation soared and the Fed sat on its hands and delayed normalizing monetary policy. This will always be viewed as a major policy blunder, despite the Fed’s efforts to the contrary. Since then, Charlie and I teamed up and wrote several updated papers recommending changes in the Fed’s Strategy. The latest was published by the Wall Street Journal less than a month ago (“What the Federal Reserve Can Do to Help Itself,” July 24, 2025). Charlie passed away last week. I wish he was still around to see how the Fed’s newly revised statement in many ways reverted back to the 2012 Consensus Statement that he was so instrumental in crafting. We would be having a very lively conversation.

Levy Sees Trump Nominee Miran Pushing for Radical Changes in Governance of Fed

Here's a Podcast I did with Kathleen Hays on her Podcast Central Bank Central. We dig into some issues that will emerge when the Senate Banking Committee holds confirmation hearings on Stephen Miran, President Trump's nominee to be a Federal Reserve Governor. While financial markets are focusing on whether Miran's favoring lower rates may tilt the Fed toward monetary easing, far more important is Miran's dramatic proposals to reform the Federal Reserve's governance that could materially change its monetary policy deliberations as well as bank supervision and regulation.