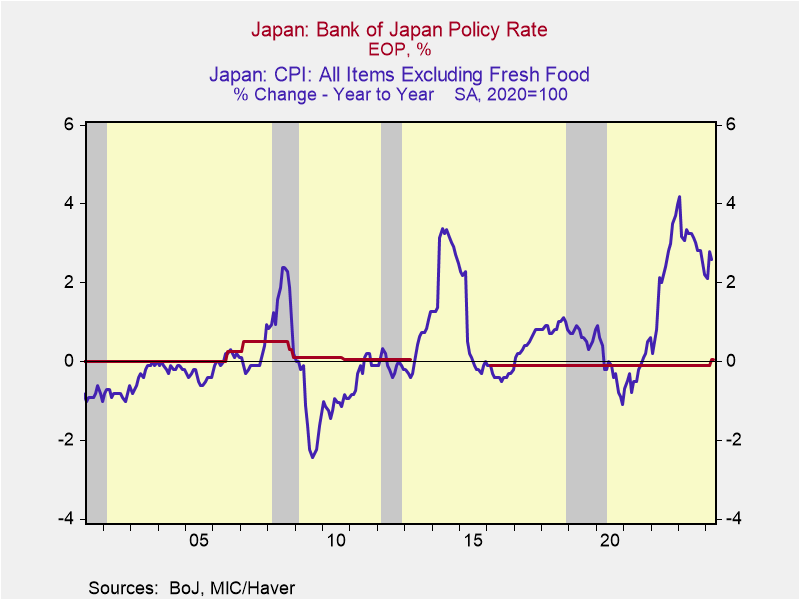

Thesis: The Bank of Japan’s policy of zero interest rates and ongoing asset purchases is contributing to a weak yen and harming Japan’s economy. Raising the BoJ’s policy rate toward its 2% target would contribute to an appreciation of the yen and boost the consumer and the economy. The BoJ’s policy rate has been zero or slightly negative for years and its massive asset purchases continue to balloon its balance sheet. This has served to distort financial markets but has not stimulated economic activity. The BoJ’s policy rate is now more than 2 percentage points below inflation. In other advanced nations, a rise in the central bank policy rate involves tighter monetary policy that weakens domestic demand. In Japan, following many years of zero or negative rates and asset purchases, normalizing monetary policy would enhance economic performance.

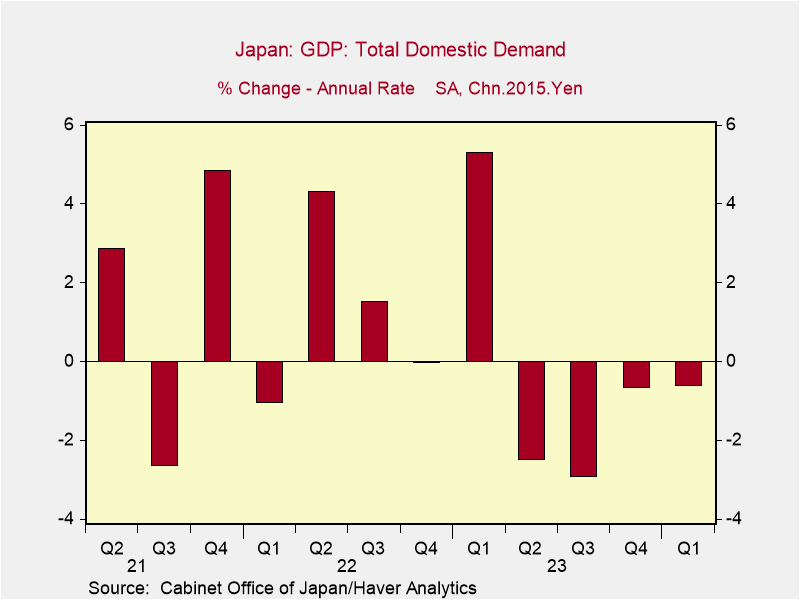

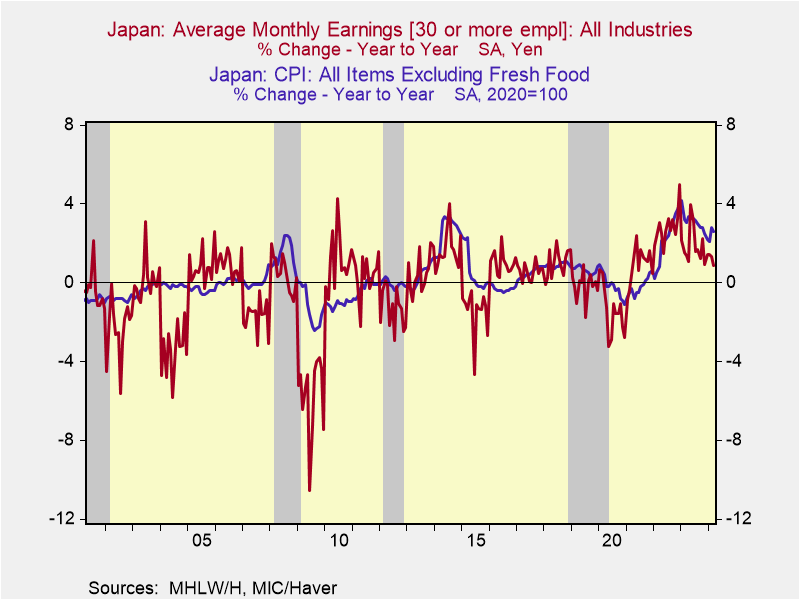

Japan’s economy has struggled in the last year. Private consumption and gross business capital formation have each fallen in the last four consecutive quarters, reducing domestic demand (Chart 1). 2024Q1 was notably weak, with a 2% annualized decline in real GDP. Earnings have fallen behind inflation, cutting into purchasing power (Chart 2).

Chart 1. Japan Domestic Demand Chart 2. Earnings and Inflation

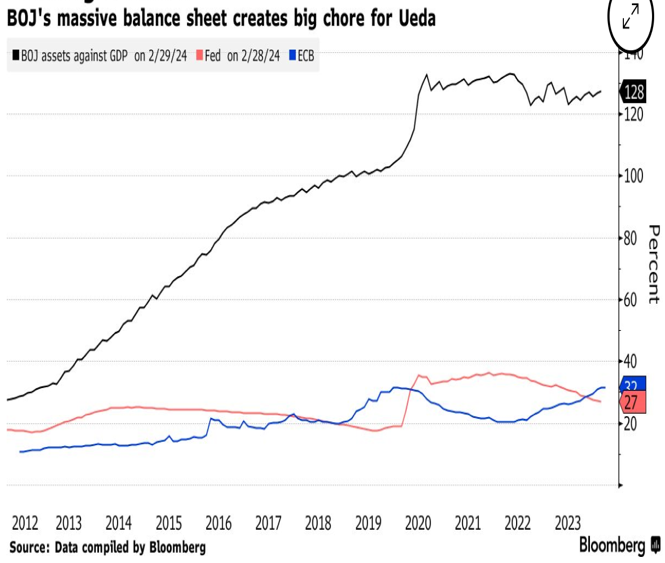

The BoJ’s persistent zero (or slightly negative) interest rates have failed to stimulate aggregate demand and have served mostly to suppress debt service costs (including the government’s) and distort financial markets and economic decisions. The BoJ’s bloated balance sheet (its assets and liabilities) is dramatically higher as a percent of GDP than the Fed’s or ECB’s and magnitudes higher that any measure of reasonableness (Chart 3). Its asset purchases have created excess reserves in the banking system, the largest portion which are loaned back to the BoJ. The BoJ officially pays interest on excess reserves, which is tied to the BoJ’s policy rate and thus until recently has been zero. Commercial banks pay close to zero yields on deposits and generally have set rates on mortgages and consumer loans that provide positive returns to banks. Consumers lose from the BoJ’s policies.

Chart 3. The BoJ’s Balance Sheet/GDP Chart 4. The BoJ’s Policy Rate and Inflation

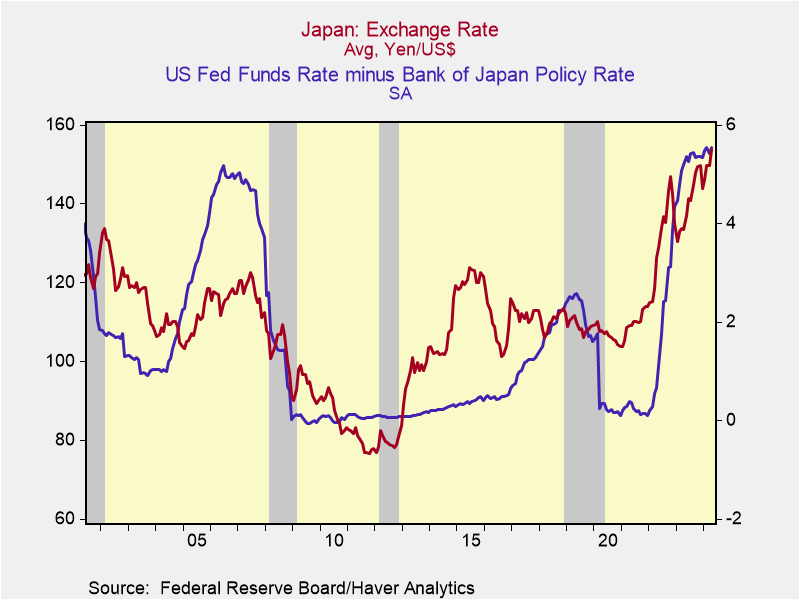

The divergent policies of the BoJ and the Fed have contributed to the marked weakness of the yen. In particular, the yen depreciated as the Fed raised rates in 2022 while the BoJ maintained a slightly negative real policy rate and its forward guidance suggested no future change. Even as the BoJ eased its yield curve control program, which allowed JGB yields to rise, the BoJ continued its asset purchases and the yen depreciation continued. Presently, the BoJ’s policy rate is more than 2 percentage points below inflation while the Fed’s policy rate (5.25%-5.5%) is roughly 2.5 percentage points above PCE inflation. Ex ante real JGBs are well below real US Treasury yields, although the comparison is clouded by the wide range of measures of Japanese inflationary expectations.10-year JGB yields have risen close 1% but inflationary expectations vary widely among different surveys and market-based measures. BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has indicated that longer-run inflation expectations are around 1.5%. 10-year Treasury bond yields of 4.5% are roughly 2 percentage points above inflationary expectations of 2.5%.

Chart 5. The Yen and Fed Funds Rate minus BoJ Rate

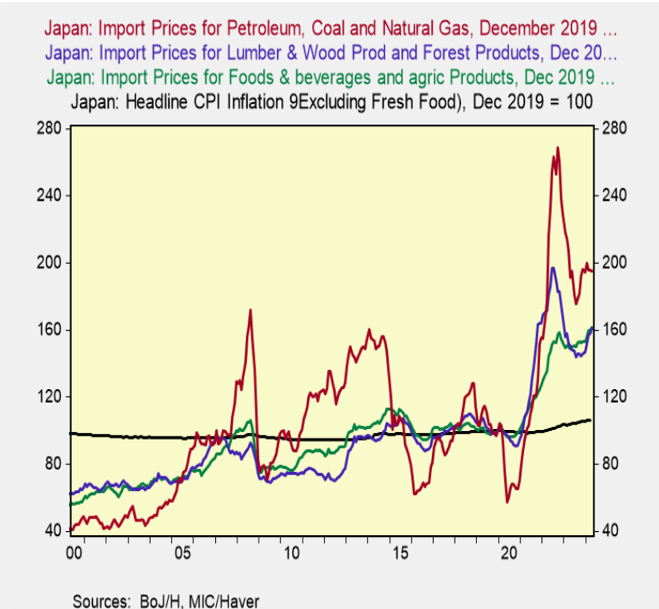

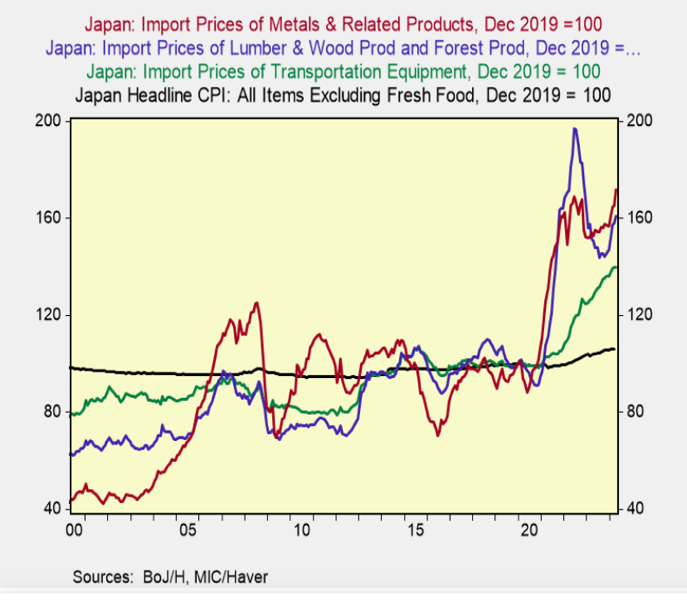

The weaker yen has benefited exporters by lowering their costs of production relative to overseas producers, but has raised the costs of imports. Japan’s imports are a relatively high 18% of GDP. Japan imports nearly 100% of its oil and energy whose transactions are primarily US dollar-denominated. Prices of imported goods have risen dramatically: Chart 6 shows the cumulative price increases of goods that are consumer-oriented and Chart 7 shows cumulative price increases of goods used in production. Prices of oil and energy imports are included in Chart 6, but they affect production just as much. These high prices of imports have dented consumption and production, and they have also weighed on confidence.

Charts 6 and 7. Prices of Imported Goods, Consumer and Production-Related

Based on the higher inflation and rising inflationary expectations, and the burdens the weaker yen is imposing on Japan’s economy, the BoJ would be wise to raise its policy rate toward its 2% target and provide forward guidance that its intention is to normalize monetary policy. This would involve raising rates and implementing a gradual program of reducing its balance sheet. While the rate increases should begin immediately and continue through year-end 2025, the balance sheet adjustment necessarily must be slower. There are currently close to 3 trillion yen in excess reserves, and the BoJ holds large amounts of long-duration assets, including corporate bonds, and it also holds ETFs of equities, so a gradual unwind of the balance sheet would likely involve a 10-year program.

As the BoJ raises interest rates, commercial banks will profit from the sizable interest they receive from the BoJ on excess reserves. The steepening of the yield curve and higher interest margins will facilitate higher bank yields on deposits. Japanese pensions, including those managed by the Postal Saving System, and insurance companies will benefit. Consumers will be better off. It will take years to judiciously unwind the excess reserves in the banking system, such that bank lending is unlikely to be inhibited. The BoJ understands the negative impact of the weak yen on Japanese consumers and the economy. It’s only a matter of time before it raises rates.

Confidence will build as evidence shows economic improvement as the BoJ increases rates toward inflation and the yen appreciates. This will reinforce the yen and the domestic economy. The marked appreciation of the Nikkei has already begun to anticipate these favorable outcomes.