Inflation in the U.S., Europe, and the UK has fallen from very high levels but remains above the central banks’ goals of 2%. Following the Fed’s, Bank of England’s (BoE’s) and European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) painful experiences of failing to forecast their higher inflations and then being forced to raise rates aggressively, they look forward to lowering their policy rates. Japan also experienced a sharp rise in inflation from near-zero that is now receding but remains above 2%, and following an extended period of negative and now zero rates, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) contemplates raising its policy rate.

When will it be appropriate for the Fed, ECB, and BoE to lower rates, and for the BoJ to raise rates? The answer varies, as each central bank faces far different circumstances.

The Fed’s, ECB’s, and BoE’s policy rate is above inflation, but by varying degrees, while the BoJ’s real policy rate remains negative. Current economic conditions vary significantly in the U.S., Europe, the UK and Japan, as do their productivity and potential growth prospects that affect their neutral rate of interest. While the Fed has a dual mandate (2% inflation and maximum inclusive employment), the BoE and ECB have single inflation mandates of 2%, but they tend to respond to real economic conditions as well. The Fed and the other CBs recently have emphasized their commitments to their 2% inflation target, but it’s not entirely clear whether each would willing to pursue a monetary policy that would lower inflation to 2% if doing so may damage economic conditions. There are also currency considerations, as the US dollar has remained strong while the Japanese yen has been notably weak.

Inflation and Policy Rate Comparisons

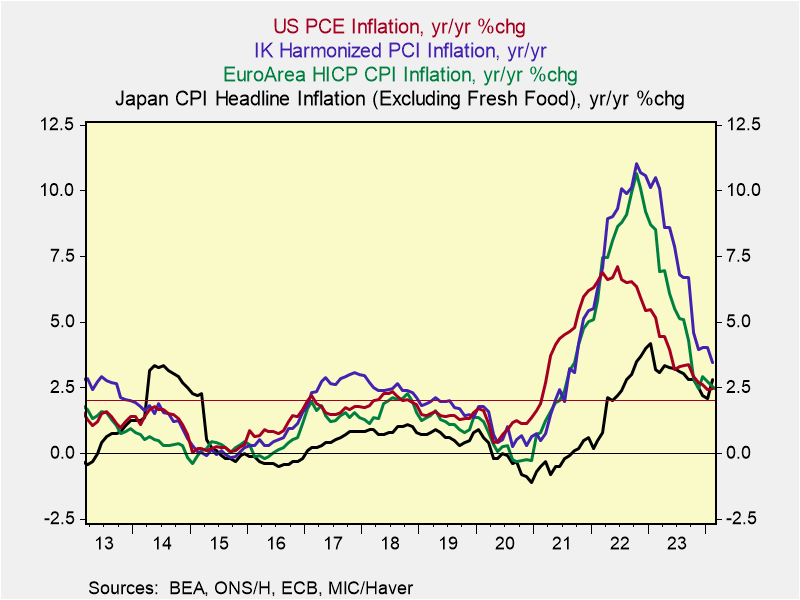

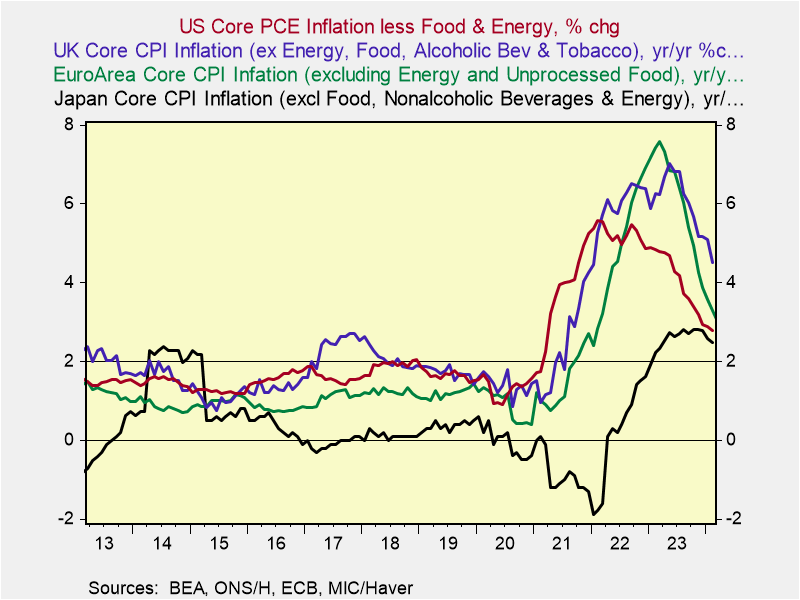

Inflation comparisons are shown in Charts 1 and 2 for both headline and core measures, and a 2% reference line for target inflation. The U.S.’s inflation is based on the PCE Price Index, the Fed’s preferred measure, while the others are CPI inflation. While inflation has subsided from high peaks, it remains above central bank targets. It soared the most in the UK and Europe. In the U.S., PCE inflation peaked at 7.2%, while its CPI inflation, which measures consumers’ out-of-pocket expenses, peaked at 9%. Japan’s inflation temporarily jumped to 4%. Currently, the UK currently stands out with the highest headline (3.8%) and core (4.7%) inflation.

Charts 1 and 2. International Comparison of Inflation

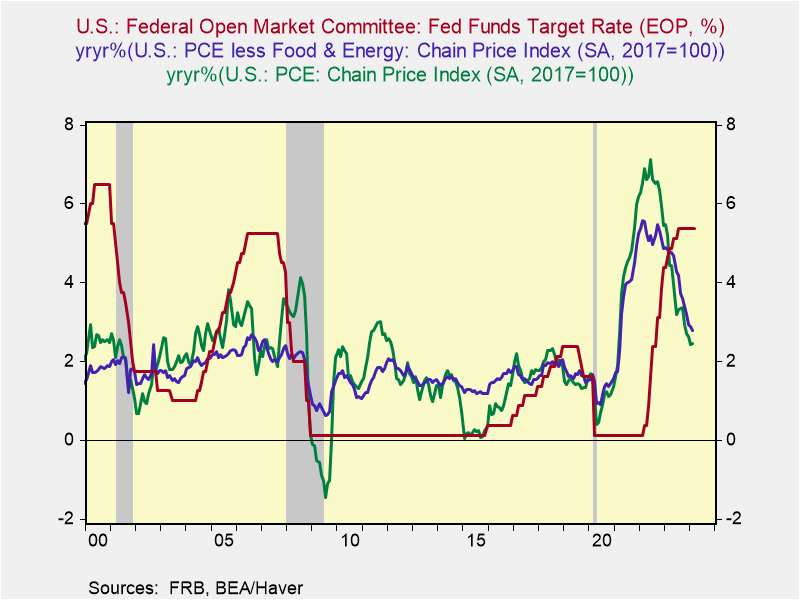

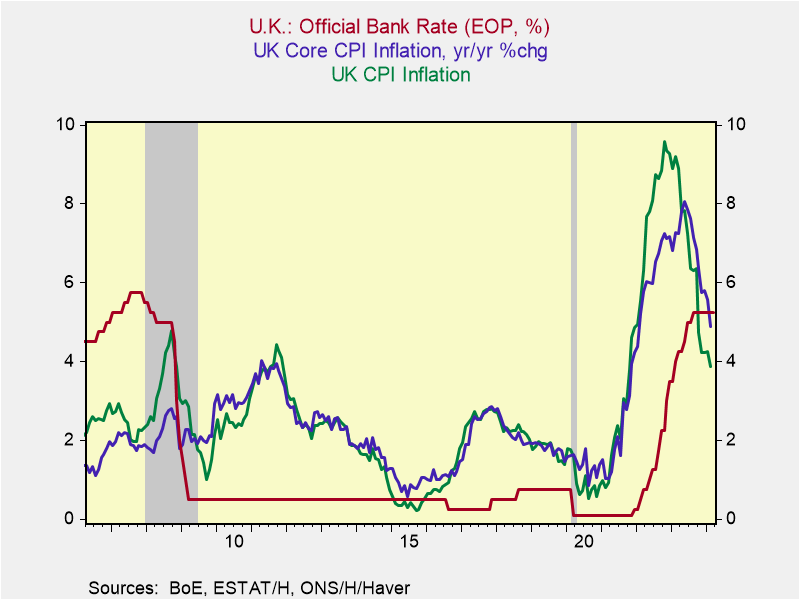

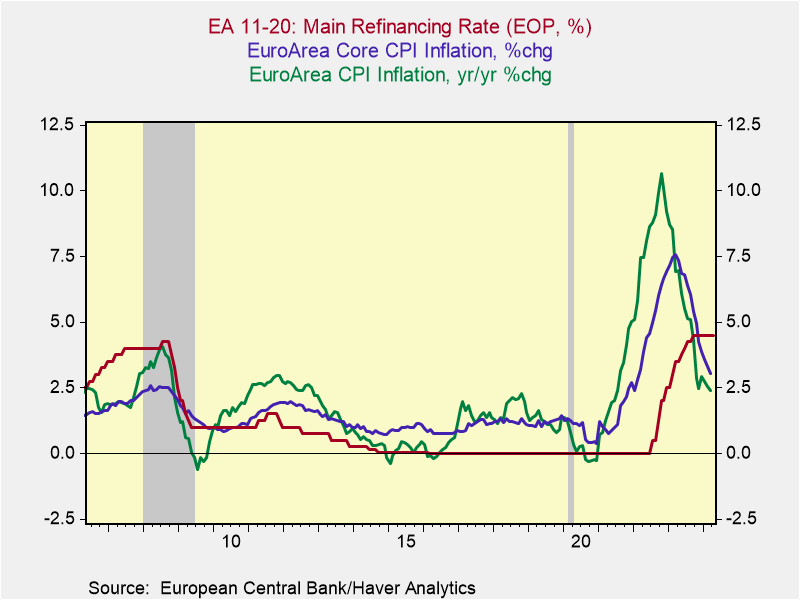

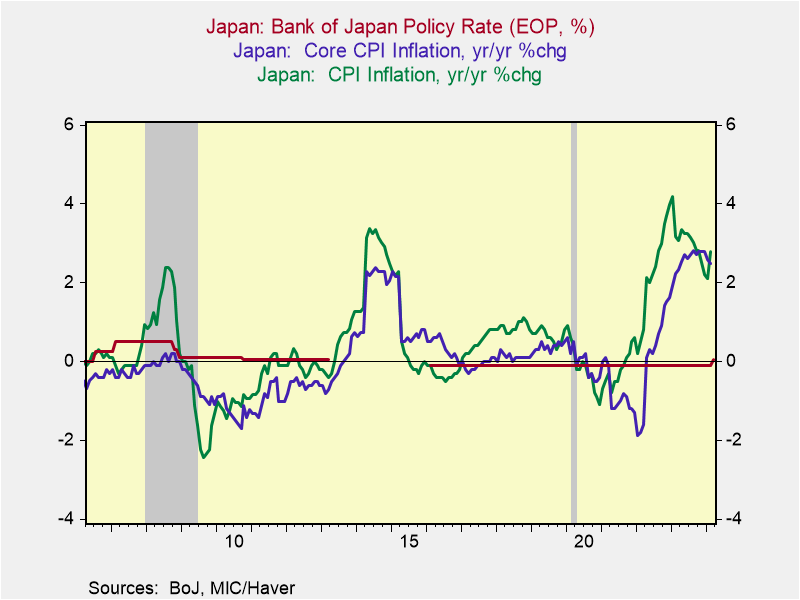

Charts 3-6 show the central bank policy rates of the Fed, ECB, BoE and BoJ relative to inflation in the U.S., the EuroArea, the UK and Japan. The Fed, BOE and ECB failed to respond on a timely basis to the surge in inflation and then raised rates aggressively in 2022-2023. The BoJ applauded Japan’s rise in inflation following a sustained period of near price stability, viewing it as a sign of economic improvement and hoping that it would lift inflationary expectations toward its 2% target.

Chart 3. Fed Funds Rate and U.S. Inflation Chart 4. BoE Policy Rate and Inflation

Chart 5. ECB Policy Rate and Inflation Chart 6. BoJ Policy Rate and Inflation

In each case, the central bank policy rate rose above inflation in 2023 through a combination of rate hikes and declines in inflation—in March for the Fed and later for the BoE and ECB. The BoJ raised its policy rate from minus 10 basis points to 0% in January 2024. Currently:

*The Fed’s 5.4% Fed funds rate (target rate is 5.25%-5.5%) is 2.7 percentage points above headline inflation and 2.6 percentage points above core inflation (Chart 3).

*The BoE’s 5.25% policy rate is 1.5 percentage point above headline inflation and 0.5 ppt above core inflation (Chart 4).

*The ECB’s 4.5% refi rate is 2.1 percentage points above headline and 1.8 percentage points above core inflation.

*The BoJ’s policy rate of 0%, recently increased from -10 basis points, is more than 2.5 percentage points below yr/yr inflation.

Assessing central bank monetary policy

The Fed, ECB and BoE have emphasized their commitments to reducing inflation to 2%. The challenge they face is determining the appropriate policy to achieve those goals. Recently, Fed Chair Powell and other FOMC members have characterized Fed monetary policy as restrictive, based on the observation that the real Fed funds rate is higher than any point since before the financial crisis. If inflation recedes further as FOMC members project, the real policy rate would rise further. The ECB and BoE also view their policies as restrictive and project that inflation will recede.

The critical issue is what policy rate constitutes “restrictive” monetary policy and what is neutral. That’s a complex issue, reflecting inflation, inflationary expectations and the neutral rate of interest, which is influenced by economic conditions, productivity and potential growth, among other factors, and varies among the nations and their central banks.

Inflationary expectations in the U.S., Europe and the UK remain modestly above 2% and have been relatively sticky. In the U.S., market-based expectations of 10-year inflation are 2.3% while survey-based expectations are much higher, reflecting in part the 3.6%annualized PCE inflation in Q1 that halted the earlier trend of receding inflation. The University of Michigan consumer inflation expectations one year from now jumped to 3.5% and five years from now to 3.1%. The FRB of New York consumer surveys put inflation one year ahead at 3.0% and 5 years ahead at 2.6%. The sticky inflation has forced the Fed to back off its projection that three 25 basis point rate cuts in 2024 would be appropriate, and instead say it has delayed any rate cuts. Favorably, the Fed has confirmed its intention to reduced inflation to 2%. In Europe, a recent ECB consumer survey of 3-year ahead inflation was 2.5% for the median, but the mean expectation was substantially higher. Bloomberg survey of UK 1-year ahead inflation was 3.0%, reflecting sticky inflation. In Japan, the sustained period of near-zero inflation prior to the pandemic has weighed heavily on inflationary expectations, despite persistent efforts to raise expectations to 2%. Following years of nearly zero inflation, those expectations are rising, ever-so-gradually. In the latest survey, 83.3% of consumers expect prices to rise in one year and 80.6% expect prices will rise in 5 years. This doesn’t seem like much from the western perspective, but represents change in Japan, where expectations of true price stability had become the norm.

Real economic performance

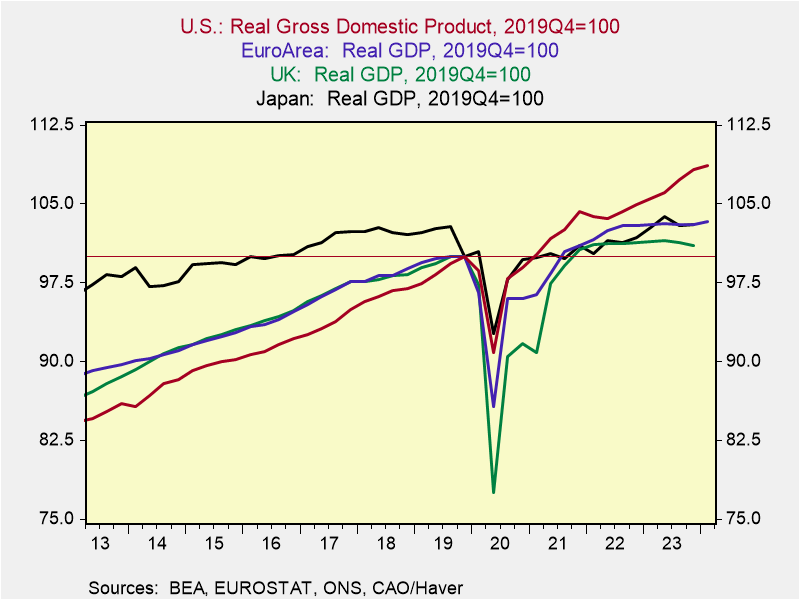

Europe and the UK have begun to recover from mild recessions in 2023, with growth in 2024Q1. Japan has continued to grow modestly faster than its longer-run potential, and U.S. economic growth has begun to simmer down following strong growth in 2023. The cumulative out-performance of the U.S.—both prior to and following the pandemic–has been dramatic, as shown in Chart 7.

Chart 7. International Comparisons of Real GDP, 2019Q4=100

EuroArea real GDP bounced back in 2024Q1 with 1.3% annualized growth following mild recession in 2023 marked by annualized RGDP declines of 0.2% in both Q3 and Q4. While consumption and gross business capital formation rose modestly in 2023, exports (-2.8%) and imports (-2.4%) both fell. Germany has been Europe’s underperformer. While its RGDP rose 0.9% annualized in 2024Q1, it fell 0.2% 2023 Q4/Q4, with sizable declines in both gross fixed capital investment (-0.8%) and exports (-3.3%). France and Italy both grew modestly in 2023 Q4/Q4 (+0.8% and +0.7%, respectively) and their pace of growth picked up in 2024Q1 (+1.2% and 1.2%, respectively). Spain was the EU’s outperformer, with 2.1% growth in 2023 and 2.9% in 2024Q1, led by healthy gains in consumption and gross capital formation but relatively flat exports. This change in economic leadership in Europe requires close scrutiny.

The UK economy also began recovering from 2023 recession, with reported increases of RGDP of 0.3% in January and 0.1% in February, following quarterly declines of 0.5% annualized in 2023Q3 and 1.2% in Q4. In 2023, notable weak sectors included exports (-7.6% in Q4/Q4) and housing construction that offset healthy gains in business investment in plant and machinery. The UK has a long way to recover. Its RGDP remains 1% below its 2019Q4 pre-pandemic level, as cumulative declines of 5.4% in exports and 2.1% in private consumption have offset 4.8% increases in gross capital formation (minus dwellings).

Japan’s economy grew at a healthy, above-potential rate of 1.3% in 2023 Q4/Q4, driven by strong gross domestic fixed capital formation (+4.2%) and exports (+3.7%) but modest declines in private consumption. In its most recent Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices Report released April 31, the BoJ projects that Japan’s economic growth will continue to exceed its estimate of longer-run potential through 2025, with resilient consumption supported by government efforts to offset higher gas prices, accommodative financial conditions that support continued employment and wage gains, healthy corporate profits and rising exports.

The U.S. enjoyed strong 3.1% RGDP growth in 2023 Q4/Q4, defying earlier expectations. Outsized gains in employment (4 million, averaging 333,000 per month) fueled rising personal income and consumption, business fixed investment posted gains and residential investment recovered following declines in 2022, and exports rose modestly despite flat global trade volumes. Growth slowed in 2024Q1, but not as much as the 1.6% annualized rise in RGDP suggests. Final sales to private domestic private purchases rose 3.1% in Q1, but real GDP was dragged down by slower inventory building and a wider trade deficit (exports rose 0.9% annualized while imports surged 7.2%). Employment gains slowed to 175,000 in April.

Economic performance, real rates and monetary policy

The neutral policy interest rate varies significantly across nations, reflecting differences in trends in productivity, potential growth, demographics and other factors. Based on recent and expected performance, the neutral policy interest rate is presumed to be the highest in the U.S., followed by the UK and the EU. Unique circumstances in Japan make the BoJ’s neutral rate more of a puzzle.

In the U.S., even though the Fed has the highest real policy rate since before the financial crisis, the economy has been resilient, growing faster than the Fed’s estimates of longer-run sustainable potential, calling into question whether monetary policy is as restrictive as the Fed suggests. As I argued in a recent Wall Street Journal

article, following several decades of a secular decline in the neutral rate of interest amid weak productivity gains, the neutral rate has risen reflecting the healthy economic growth, and a pickup in productivity and potential growth, which suggests the Fed has less room to ease rates and remain consistent with its objective of lowering inflation to 2% (“The Fed’s Latest Problem: A Strong Economy”, March 4, 2023).

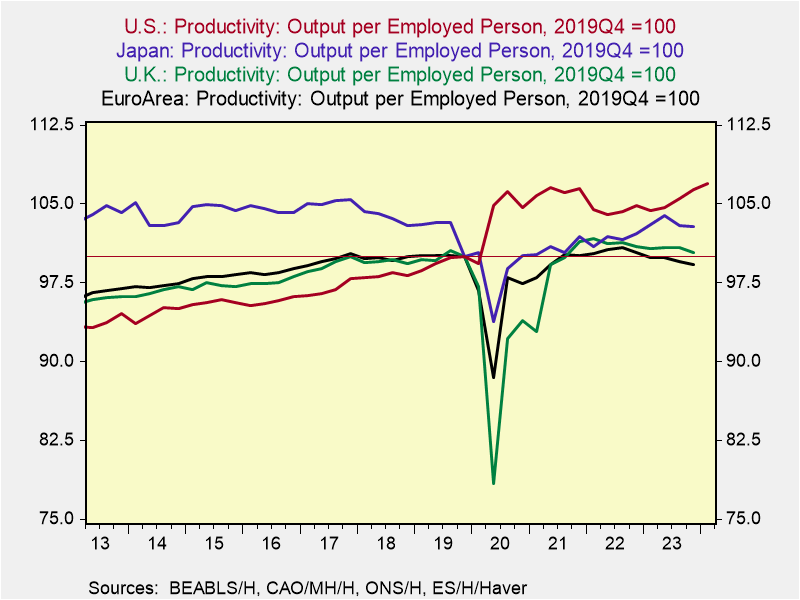

Associated with its stronger economic growth, productivity has strengthened in the U.S. Its average annualized gain in the three years before the pandemic was 1.7%, a marked increase from its annualized 0.7% gain in the prior six years, and has continued to rise at a healthy clip, although the aggregate data have been highly volatile, buffeted by large swings in employment in the low productivity services industries and the shift from full-time to pull-time work. Productivity gains have been healthy in Japan, but they have languished in Europe and the UK (Chart 8).

I estimate intermediate sustainable potential growth in the U.S. to be at least 2.25% far above the Fed’s current 1.8% estimate of longer-run sustainable growth. Higher real expected rates of return associated with higher productivity and potential growth are attracting foreign capital and supporting a stronger U.S. dollar.

Chart 8. International Comparisons of Labor Productivity

In contrast, productivity and growth have faltered in the EuroArea. Combined with unfavorable demographics affecting labor force growth, Europe’s outlook for sustainable potential growth has diminished, likely into the 0.75%-1.0% range. Of note, Germany had been Europe’s engine of economic growth, but that position began to erode before the pandemic, and in recent years, it has faced decided economic weakness and it lacks a viable strategy for its beleaguered automotive and energy-intensive industrial manufacturing sectors. Such potential growth is less than one-half of the U.S.’s. This is associated with a lower natural rate of interest and a weaker Euro.

A similarly soft productivity and growth pattern has unfolded in the UK, which has experienced a flattening of its labor force, despite a pickup in immigration. The IMF estimates UK potential growth to be 1.5%. Japan’s labor productivity of its working age population (age 16-65) is among the highest of all advanced nations. However, its healthy gains in productivity have been offset by weak demographics, marked by a declining and aging population that is reducing its labor force and low immigration, and traditionally Japan has not relied heavily on foreign workers.

The Outlook for Monetary Policy

The Fed has appropriately signaled that will delay any cut in rates. This is wise since inflation has backed up and interrupted disinflation while gains in employment and aggregate demand remain healthy. Of note, in Q1, nominal GDP rose 4.8% annualized and 5.5% yr/yr, consistent with sticky inflation, while real final sales to domestic purchasers (C+I) grew 3.1% annualized. Payroll growth slowed to 175,000 in April, but that pace of job gains is consistent with continued healthy growth in GDP, unless productivity slows abruptly, which seems unlikely.

The Fed remains fully data-dependent. Powell has stated that there is a very low probability that the Fed’s next rate move is up, and most Fed members await slower growth and a resumption of declining inflation they have projected so they can lower rates. (Whether the economic slowdown that seems to be unfolding is attributable to the Fed’s monetary tightening or merely a moderation from unsustainably fast growth is open to debate.) I continue to expect that will unfold and the Fed will begin cutting rates later this year.

However, the Fed has less room to lower rates. If the real neutral rate is 1.5%-2%, then eventually lowering rates to 3.5%-4% would be consistent with its 2% inflation target. In its latest Summary of Economic Statistics (SEPs), FOMC members estimated the longer-run fund funds rate to be 2.5%. The Fed tends to lag, and that estimate will rose very slowly.

The ECB has the most room to lower its policy rate, which is far above current inflation (Chart 6) while its neutral rate presumably has declined as its potential growth has diminished. Even though Europe’s economy is recovering from mild recession, it faces significant challenges. The ECB is expected to begin lowering rates mid-year 2024 and lower rates significantly through year-end 2025, and below 3% by mid-2026.

In the UK, even though inflation (4.6% headline and 3.7% core) remains far above the BoE’s 2% target, the BoE has signaled that it will begin cutting rates in June from its current 5.25% policy rate. The BoE’s decision revolves around two issues: first, the BoE places a high priority on maintaining the recovery from its recessionary conditions of 2023, and second, it expects inflation to fall significantly. This outlook is based on the BoE’s expectations that growth of aggregate demand will be weak, following its sharp deceleration in the second half of 2023, and the roll-off of the high monthly inflation data of 2023. But with inflation so high, providing forward guidance that it will be lowering rates is risky for the BoE.

The BoJ is gearing up to raise rates gradually and normalizing monetary policy to what it hopes is a new era of 2% inflation. Raising rates would also provide support for the battered yen, which is 155/USD after reaching 160/USD. Modest increases of interest rates toward 2% would elicit adjustments in financial markets. However, the BoJ’s sustained maintenance of a slightly negative policy interest rate since 2015 and expanded balance sheet had little apparent impact on real economic activity and inflation. As such, it seems unlikely that raising rates will have much effect.

The sequencing of these central bank policy changes will influence currencies. The yen is expected to strengthen. Monetary easing by the BoE and ECB before the Fed may keep the pound and Euro weak, although future markets have already begun to price in these changes. Once financial markets begin to anticipate that the Fed will lower rates, the US dollar is likely to weaken, but only modestly, in light of the outperformance of the U.S. economy and high expected rates of return on capital.