In an article published in the Wall Street Journal last Monday, I argued that there has been a pickup in productivity and sustainable potential real growth, which has raised the natural real rate of interest. These trends imply that the Fed’s real policy rate of 2.6% (the Fed’s current target of 5.25%-5.5% minus the 2.8% core PCE inflation) is not as restrictive as the Fed perceives, limiting the magnitude of interest rate cuts appropriate to achieve the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

The Fed’s view, as reflected in Fed Chair Powell’s testimony on the Fed’s semiannual Monetary Policy Report (MPR) to Congress, is that monetary policy is restrictive and will generate a significant slowdown in economic growth below potential that will lower inflation to 2%. Following this, important data releases throughout the week confirmed the continued health in labor markets and strength in household balance sheets that will support ongoing consumer spending. Later in the week, I also had the honor of discussing these issues with Larry Summers at an investment conference in Phoenix, Arizona. His views on the economy, real interest rates, and the Fed were similar with mine — and capped off a week full of insights.

WSJ Commentary. In my WSJ piece (“The Fed’s Latest Problem: A Strong Economy,” March 4, 2024),

I fully understand the speculative nature of my assessment that productivity has picked up and the natural real rate of interest is higher than the Fed perceives. The productivity data bounce around a lot, and it’s too early to confirm any sustained pickup. The assessment of stronger productivity gains is based on mounting anecdotal evidence of rapid implementation of technological innovations such as generative AI, the efficiencies generated by heightened labor market mobility, the sizable shift in business investment toward software and R&D, and the big jump in new business formation. In addition, the natural real rate of interest is unobservable, and efforts to estimate it are iffy. Nevertheless, the assessment seems consistent with recent conditions in which real GDP has grown 3.1%, substantially faster than the Fed’s 1.8% estimate of sustainable potential real GDP growth, and the unemployment rate has been comfortably below the Fed’s estimate of a 4.1% natural rate of unemployment, despite the Fed funds rate at its higher level since before the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis.

Despite these caveats, my assessment is that the negative real Fed funds rate and low bond yields during the post-GFC expansion were the aberration, and interest rates have normalized. As shown in Chart I, the 1990s were characterized by high real interest rates, associated with a productivity boom and strong economic growth.

Important data. Labor market data remain healthy, with continued healthy increases in employment in February and the JOLTS data in January indicating softening demand for labor but generally tight conditions. Establishment payrolls rose 275,000 in February following the downwardly revised 229K in January, maintaining the 1.8% yr/yr rise in jobs. This is very healthy, by any measure. Aggregate hours worked in February rose 1.0%, more than offsetting the 0.6% decline in January. This will lift wage and salary and disposable personal income. The Household Survey, also released last week, was softer: On a positive note, the civilian labor force rose 150K, but employment fell 184K and unemployment rose 334K. There has been a noted divergence in the Household and Establishment surveys in recent months.

The JOLTS report for January registered modest declines in job openings and hires and a further modest decline in the quit rate, which combined indicated that while labor market demand continues to soften and close the gap with labor supply, labor markets remain healthy and relatively tight. These assessments were echoed in the Fed’s MPR and Powell’s testimony to Congress. Of note, the job opening ratio of 5.3% — total job openings as a percent of total employment plus job openings — remains well above its pre-pandemic level, while the hiring and quits rates are modestly below their pre-pandemic levels.

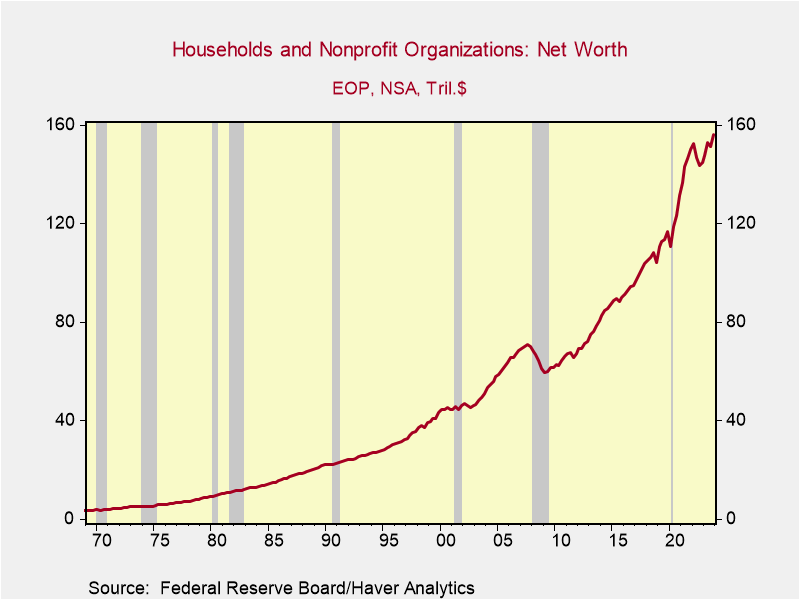

The Fed published its Financial Accounts of the United States for 2023Q4 Thursday, and the report was striking. Household net worth (net of all debt) increased $4.8 trillion in Q4, culminating a $11.6 trillion (8%) increase in the four quarters of 2023 (Chart 2). The stock of household net worth is 7.6 times the annual flow of national disposable personal income. Of the total household net worth, $31.8 trillion, or only 20.3%, is owner equity in real estate. While this huge magnitude of wealth is unevenly distributed, a sizable number of households have a significant amount of net worth that is flowing into the economy and raising the propensity to spend (“Consumption and Household Net Worth,” December 21, 2023). As I note below, it’s no wonder consumers are spending and the rate of personal saving relative to disposable personal income is low.

The Fed’s Monetary Policy Report and Powell’s Congressional Testimony. The Fed’s thorough report described evidence of healthy economic growth, tight labor markets, and the favorably lower inflation trend. Powell echoed these themes in testimony and underlined the Fed’s goal of reducing inflation to 2%. Consistent with recent public statements, Powell characterized monetary policy as restrictive, presumably reflecting the high real Fed funds rate, that the Fed projects will slow real GDP growth to 1.4% in 2024 (Q4/Q4) and thereby lower inflation to 2%.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Fed’s MPR is the report on “Monetary Policy Rules in the Current Environment” that appears at the end of Part 2 on Monetary Policy. It describes equations for the Taylor Rule and four other interest rate rules for conducting and assessing monetary policy. In keeping with the Fed’s heavy reliance on discretion, the report discusses the limitations of using simple rules for the conduct of policy but does not describe how using the Taylor Rule or other rules would have resulted in better monetary policy and economic outcomes. The concluding chart of historical federal funds rate prescriptions from the simple policy rules shows how the Fed was way behind in raising rates in 2021-2022 relative to the rules’ prescriptions, and how the Fed funds rate currently is very close to the prescribed rules. This observation seems consistent with my assessment that the natural real rate is higher than the Fed perceives which reduces the magnitude of room to lower rates.

An Educational Investment Conference. On Thursday, I participated in an investment conference in Phoenix, Arizona attended by 200+ people involved in investments and sponsored by Smead Capital Management and others. In the first session, I was honored to share the stage with Larry Summers in a discussion about economic conditions and the Fed.

In response to an opening question about the economy, Summers was positive, and tackled head on the Fed’s surprising resilience in the face of its aggressive rate increases. He detailed how all of the conditions upon which he had based his 2016 secular stagnation hypothesis (“The Age of Secular Stagnation: What It is and What to Do About It,” 2016) — insufficient demand, excess saving, low natural interest rates, as originally hypothesized by Alvin Hanson in the 1930s and subsequently used by Bernanke (2003) and more recently to explain the anemic recovery from the Financial Crisis by Ken Rogoff, Robert Gordon, and Paul Krugman, all of whom argued the need for more government fiscal stimulus to boost demand) — have reversed.

Summers agreed with me on the pickup in productivity and sustainable growth, citing anecdotal evidence of technological innovations efficiencies that were transforming the economy, and argued that natural rate of interest was “somewhere between 4% and 4.5% rather than Fed’s estimate of 2.5% [he added inflation]…so it’s no wonder that the Fed’s aggressive rate increases haven’t slowed the economy.” He stated that it’s not that his secular stagnation hypothesis was wrong; rather, he quoted Keynes “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

In response to Summer’s discussion of secular stagnation, I noted that much of the anemic recovery from the Financial Crisis (marked by high saving rates and insufficient demand) and low inflation reflected household efforts to replenish their balance sheets that had been severely damaged by the collapse in home values and household net worth during the GFC and the unwise buildup of $1.4 trillion in home equity loans. I juxtaposed those dire conditions with the current relative healthy household balance sheets and soaring household net worth. It should be no surprise that the current rate of personal saving is well below the rates that persisted following the Financial Crisis, and that growth in aggregate demand is healthy. My assessment, which requires further empirical research, has far-reaching implications for the sources of the anemic recovery and low inflation that followed the Financial Crisis, which influenced the Fed’s thinking about inflation and its policies in response to the pandemic.

Summers continued to say that while he thought the government data over-stated inflation when it was high in 2021-2022, the data now are understating the underlying inflation pressures. He also expressed serious concerns about the persistent government deficits and debt, and projected higher bond yields.

The next panel at the investment conference involved a very interesting discussion of venture capitalists. As they detailed the role of VCs, the panelists brought to life how technological innovations are transforming activities and businesses in an array of industries and how risky capital was financing innovations and research. My clear walkaway is that even if the economy slows cyclically, the pace of technological innovations and implementation into commerce will continue to speed ahead.

Chart I. The Fed Funds Rate and Core PCE Inflation

Chart 2. Household Net Worth