The sustainability of the expansion and the health of the economy depends critically on consumption, which is 69% of GDP. The biggest factor driving consumption is real disposable income, which is determined by employment and wages, but it is also influenced by real interest rates and changes in household net worth. This note briefly discusses the trends in disposable income, interest rates and consumption and then focuses on household net worth and its implications.

Employment and consumption are closely correlated, with causality in both directions: businesses hire when product demand is rising, which supports personal income and spending, and they cut jobs when product demand softens. Continued job gains are highly important for the consumption outlook. A sizable portion of the population spends most of its disposable income, with the rate of personal saving now hovering around 4%.

Establishment payrolls gains slowed in recent months, and are expected to moderate further. November’s 199,000 rise in payrolls was boosted by return of 30,000 UAW workers following their strike and a 50,000 increase in government employment. Job openings and the quit rate receded back to pre-pandemic levels, reflecting the slower demand for labor and increasing worker concerns and caution. Weaker gains in employment would moderate increases in disposable personal income, which is up 3.75% yr/yr. Even as businesses continue to restructure, job layoffs have remained low. Meanwhile, employment in the Household Survey is rising faster (2.2% yr/yr) than payrolls in the Establishment Survey, perhaps reflecting the heightened mobility of labor and the expanding roll of self-employed people.

While the rise in real interest rates since 2021 has dampened consumption, the rise in household net worth has provided a valuable offset. Among the interest sensitive sectors, auto sales have held up better than expected despite significant increases in borrowing costs, while housing activity has dampened.

Motor vehicle sales have remained above a 15 million annualized pace for much of 2023, above their 14 million pace in 2022, even though the average borrowing costs reached 7.8% and over 80% of sales of new autos are debt-financed. The higher mortgage rates have weakened housing activity, slowing employment in construction and consumption of household durables. The recent significant decline in interest rates is expected to provide support to debt-financed consumption and housing demand. The rise in household net worth, particularly soaring home values, has increased the propensity to spend and has provided a valuable offset.

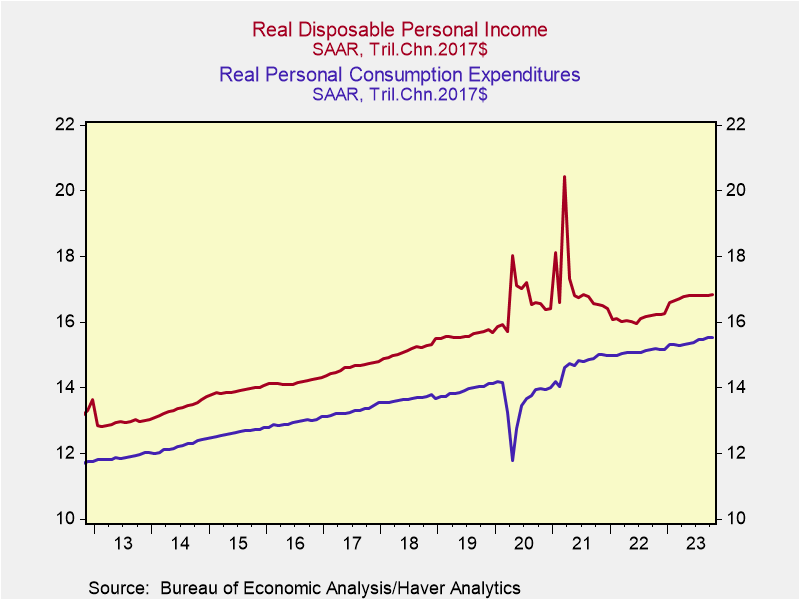

The savings cushion: important but not the whole story. The savings cushion, which has received substantial attention, is the cumulation of the rate of personal saving—the portion of disposable personal income that is not been spent. The dramatic spikes in the rate of personal saving in 2020-2021 resulted from the government’s overly generous income support responses to the pandemic while mandated shutdowns constrained spending. This bloated the cash-flow savings cushion to an estimated $2.5 trillion in 2020-2021, over 12% of disposable income. Chart 1 shows the spikes in disposable personal income were closely related to the direct transfers to individuals through the CARES Act in March 2020, the Tax Relief Act in December 2020 and the American Rescue Plan in March 2021.

As rising inflation cut into real purchasing power, consumers spent a portion of this cushion in 2021-2022, which along with ongoing healthy growth of real disposable income contributed to sustained growth of real spending. A key focus of Wall Street economists and commentators in 2023 has been estimating the remaining savings cushion and speculating on what would happen to consumption when the cushion dissipated. This led many to take a pessimistic view of consumption.

The savings cushion is largely held in liquid assets such as bank deposits and short-term money market funds and is an important source of financing spending. However, focus on the savings cushion has diverted attention from household net worth–its dramatic increases and sheer magnitude—that has a sizable impact on consumption.

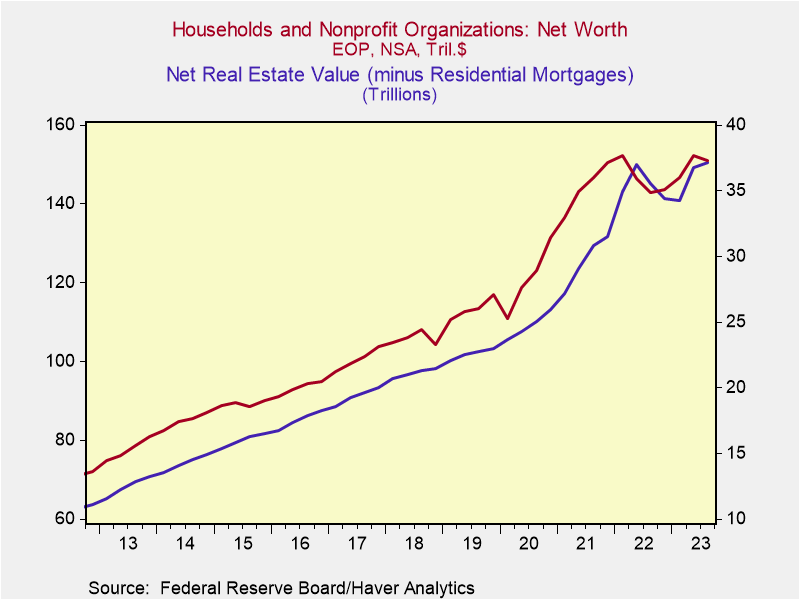

Household net worth. Household net worth, published by the Federal Reserve Board, includes the value of financial assets such as stocks and bonds and liquid assets, as well as pensions, annuities and other forms of savings, and nonfinancial assets, largely residential real estate. Since just before the pandemic in 2019Q4, it has soared by $34.1 trillion, or 29.6%, in 2023Q3 (Chart 2). It is 7.75 times the annualized flow of disposable personal income. It has continued to rise in Q4, driven by the rally in stocks, decline in bond yields that has pushed up the principal value of bonds, and particularly by the ongoing rise in residential real estate values.

Household net worth is less accessible than the largely liquid savings cushion, but is magnitudes larger and financial innovations have facilitated easy and efficient avenues for extracting cash out of assets. Borrowing against real estate wealth is readily available and does not involve negative tax consequences.

A summary of important details from the FRB’s Household Net Worth data is provided in Table 1. From 2019Q4 to 2023Q3, total household assets have increased 28.1% to $171.3 trillion from $133.5 trillion, while total outstanding debt has increased 22.3% to $20.3 trillion from $16.6 trillion. The slower growth in household debt reflects in part lower interest rates that have reduced debt service costs. Financial assets have increased 20.1% to $112.4 trillion from $93.6 trillion. Importantly, the value of real estate has soared 52.2% to $45.5 trillion from $29.9 trillion while outstanding residential mortgages has increased 22.9% to $12.9 trillion from $10.5 trillion. As a result, owners’ equity in residential real estate net of mortgage debt has risen 68% to $33.6 trillion from $19.4 trillion since 2019Q4.

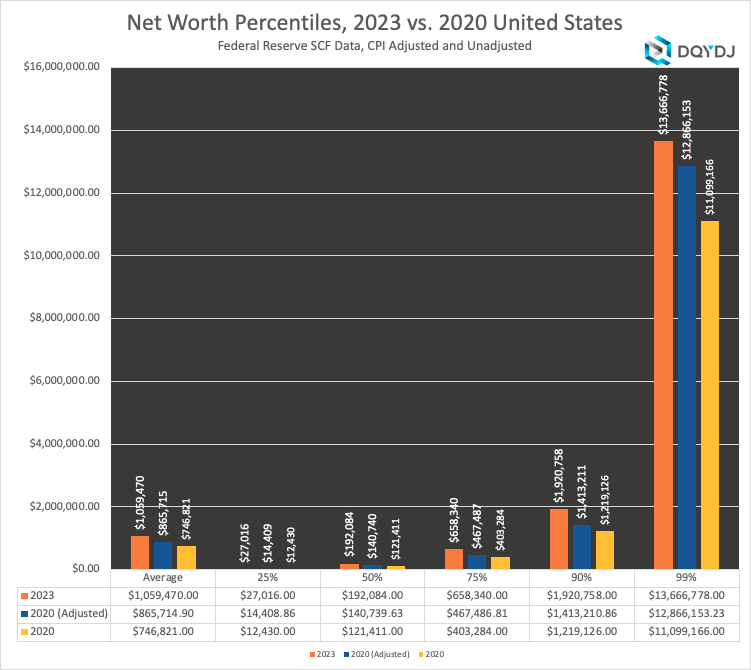

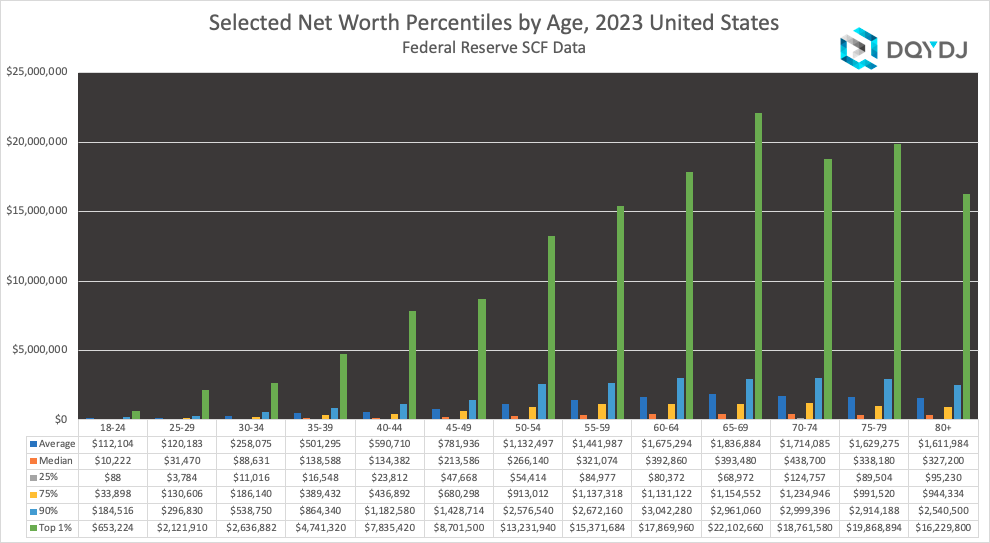

While the distribution of household net worth is highly unequal, with 66% of the net wealth held by the top 10% of households, and in general skewed toward households with high income, tend to be older and have higher educational attainment, there is a surprisingly large number of households with significant wealth. According to the United States Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for 2021, while the 50th percentile household had net worth of $166,900, the 75th percentile household had net wealth of $604,900, and the 90th percentile has net wealth of $1,623,000.

Based on 130 million households, these data suggest that in 2021 approximately 15 million households had net worth exceeding $1 million. The appreciation of asset values, particularly residential real estate, has lifted these figures significantly through 2023, as shown in the Fed’s latest Survey of Consumer Finances.

Wealth and the economy. Household net worth affects the economy through direct flows into disposable income and the economy and by changing the propensity to spend. A portion of the wealth flows directly into disposable personal income. Assets of pension funds, annuities and IRAs are distributed and redeemed, adding directly to disposable personal income. Currently there are $13 trillion in IRAs, 401(k)s and Keoghs, and people over 72 must redeem minimal amounts each year. Pensions and annuities provide a constant stream of income to retirees.

Charitable giving in 2022 was $500 billion and sizably larger in 2023, which boosts the spending and activities of charitable organizations. Intergenerational gifts within families transfer wealth to family members and increase purchasing power. Direct cash gifts up to legal limits increase spending power of recipients. Parents provide down payments to their grown children to subsidize rental costs and first home purchases, while grandparents pay for the educational costs of their grandchildren, freeing up purchasing power of the parents. These and many other avenues lift consumption and economic activity.

In addition, increases in household net worth lift the propensity to spend disposable income. Most empirical studies, many conducted in the early-2000s, have found that changes in household net worth influence the propensity to spend, with the estimated elasticity of consumption with respect to changes in wealth centering around 0.05. Key studies have found that changes in real estate values have a significantly larger impact on spending than increases in the value of financial assets such as stocks and bonds (Greenspan and Kennedy 2007). The presumption was that increases in residential real estate were considered more permanent than increases in the value of financial assets like the stock market, and that it’s easy to extract cash from real estate assets without the potential tax costs of selling stocks or bonds or redeeming money from IRAs or pensions.

A more recent paper by Karl Case, John Quigley and Robert Shiller (of the Case Shiller Home Price Index fame) published in 2013 is particularly instructive because its estimates of the wealth effect include the impacts of the sharp decline in home values around the Financial Crisis as well as their surge in the early 2000s (Case, Quigley and Shiller 2013). Based on regional and state-by-state data and using retail sales as a proxy for consumption, they estimated an elasticity of retail sales with respect to a change in real estate values (net of debt) of 0.066-0.068. This was higher than their earlier estimates conducted before the Financial Crisis. Like other studies, they found changes in the value of financial assets to have a lesser effect on retail sales, approximately .025. Of note, while their earlier study found an asymmetric wealth effect in which rising home values boosted consumption but falling home values did not, this study found a symmetrical wealth effect.

These estimates may overstate the wealth effect on consumption, since retail sales are 35% of total consumption and include a higher share of discretionary spending than consumption of services (65% of consumption), which includes spending on shelter, health care, personal and business services and involve less discretionary spending.

Nevertheless, their estimates of the wealth effect explain the very weak rebound in consumption following the financial crisis. The fiscal stimulus provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and the Fed’s imposing zero interest rates and its series of quantitative easing programs were mitigated by the negative wealth effect imposed by the 25% decline in residential real estate values from 2006Q4 to 2011Q4 and the 15% decline in stock market values over the same period (including the 31% decline in stock values from 2006Q4 through 2009Q1 that jarred confidence). As a result, the recovery of consumption from the deep 2008-2009 recession was the slowest on record.

Based on the Case-Shiller-Quigley estimated elasticities, the increase in household net worth since the pandemic, particularly the strong gains in real estate values, has lifted consumption substantially, by approximately 4%-5%. Other research has found that the wealth effect on consumption operates with a lag (Dynan and Maki 2007). The current general health of household balance sheets and low debt service costs suggests the positive wealth effect on consumption may be extended. Certainly, the positive wealth effect would be insufficient to offset an unanticipated large decline in employment or a reversal in the recent decline in inflation and interest rates, but on the margin is clearly benefiting the trend in consumption.

References

Case, Karl, John M. Quigley and Robert J. Shiller (2013), “Wealth Effects Revisited: 1975-2013”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 18667.

Dynan, Karen E. and Dean M. Maki (2007), “Does Stock market Wealth Matter for Consumption”, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Greenspan, Alan and James Kennedy (2007), Sources and Uses of Equity Extracted from Homes”, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Discussion Series 2007-20.

Chart 1. Real Disposable Personal Income and Consumption

Chart 2. Household Net Worth and Net Real Estate Value

Table 1. Balance Sheet of Households and Nonprofit Organizations

2019Q4 ($T) 2023Q3($T) chg. in $Tril chg. in %

Assets 133.5 176.5 42.8 32.0

Financial 93.6 112.4 18.8 20.1

Equities 43.4 55.4 12.0 27.6

Liquid* 3.5 7.9 4.4 125.7

Nonfinancial 39.9 58.8 15.9 39.8

Res real estate 29.9 45.5 15.6 52.2

Mortgage debt 10.5 12.9 2.4 22.9

Owners equity 19.4 32.6 13.2 68.0

Liabilities 16.6 20.3 3.7 22.3

Household Net Worth 116.9 151.0 34.1 29.1

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Note: *Deposits and money market funds

Chart 3. Household Net Worth Characteristics, 2020-2023

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors Survey of Consumer Finances, 2022.

Chart 4. Household Net Worth Percentiles by Age

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors Survey of Consumer Finances, 2022.